LILO RINKENS – APERTURA – The emergence and disappearance

“These are astonishing movements, at any rate, along an invisible space-time line, or so it seems to me” writes Rosemarie Gropp in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung on the occasion of an exhibition by Lilo Rinkens in Vienna.

__________________________

“In a book about the Japanese mentality, I read the following sentences:

All the paradoxes of Zen refer to a ‘void’ which for us (i.e. for us Europeans) seems to be nothing else but the absence of content. For the Japanese it is considered the best inner attitude. Just as the reality of this space is not to be found in its ceiling or its walls, but in the empty space, the vacuum of the mind is its true essence. Whoever could empty himself completely spiritually would be master of all situations, everything could penetrate his mind uninhibitedly.

In fact, the Japanese – practiced in the art of meditation – reacted to Lilo Rinkens’ works with the same pleasure as we Europeans normally only react to well-done comedies.

Wanting nothing, above all: wanting to understand nothing, and if you do, not with your mind, but with intuition, the noblest way of understanding.

Perhaps it helps to approach this understanding, as far as we can, to rise above private feelings, personal relationships and the vanities of life for a moment.

For the sake of your soul’s happiness, one must never be in a hurry.

The true nature of things is revealed only after one has passed through a state of complete emptiness.

The oldest of the Japanese, a Buddhist, said after seeing the film “oh darling”, something for Lilo Rinkens very surprising, he had seen, he said with a smile and a bow to her, the best porn movie of his life.

Neither of us can quickly become Japanese – much less Buddhist – but while we’re here, let’s take our first breath on the way there.”

Wolf Wondratschek

_______________________________________________

When there is little to see, I am happiest – Artist portrait of Lilo Rinken

The artist talk with Lilo Rinkens was conducted by Dr. Heike Hagemann

Born in Altenburg in 1946, the artist studied sculpture as a private student from 1977 to 1979 with Marianne Rousselle (1977-1979) and Lothar Fischer (1983-1988). From 1988 to 1989 she was a student of the famous Italian painter Emilio Vedova. In addition to regular exhibitions in galleries, including the Galerie Trampler in Munich, the artist has contributed to numerous publications, including the “Kellybriefe” with Wolf Wondratschek. The conversation with the artist took place on May 27, 2015 in her Munich studio.

HH: When did you start your art? Was there a specific occasion?

LR: I already drew as a schoolgirl, I often went to museums. I really started at the age of 30, when I already had a family. I enrolled at the academy, but that didn’t get me anywhere. So I chose my own teachers.

HH: How did you come to sculpture?

LR: I came to sculpture more by chance through my first teacher, the sculptor Marianne Rousselle, who told me: “and if it’s not sculpture, then it’s something else”. This gave me the freedom not to stick to plans and was very important for my future until today. I was with her for about four years and acquired the sculptural techniques to work in stone, wood and bronze. I remember a day of crisis, when I had already produced and sold many sculptures, the last series were huge, painted Styrofoam sculptures that were in my studio. I broke, sawed and smashed the sculptures in a fit. Today I can say in retrospect: that was too much material, it bound me mentally and physically. Not my way.

HH: Did the crisis initiate the transition to painting?

LR: My next teacher was Lothar Fischer. I also helped him with his work in the foundry. But I soon realized that I had to turn to the surface. When I sat somewhere and observed things, I felt that what touches me cannot be grasped in matter. Emilio Vedova was in Salzburg at that time, he became my next teacher. I was one of his favourite students, we also kept in touch privately. I began to paint with the same temperament as he did: it was a very excessive painting: wild, gestural, unrestrained and angry. The next turning point came when I created a very purist painting in large format, and he told the other students: “This woman works on the nothing, the nada”. This work was far from my artistic model, Vedova, but he “recognized” me, as ma says. The decisive step to my actual work.

I was not aware of this at the time – the painting contained little colour, it had a graphic character, not a painterly one – my work has been reduced more and more since then. When there is little to see, only air and thoughts, then I am happiest. Here I am today.

HH: Is there a special relationship to space, time and movement in your paintings?

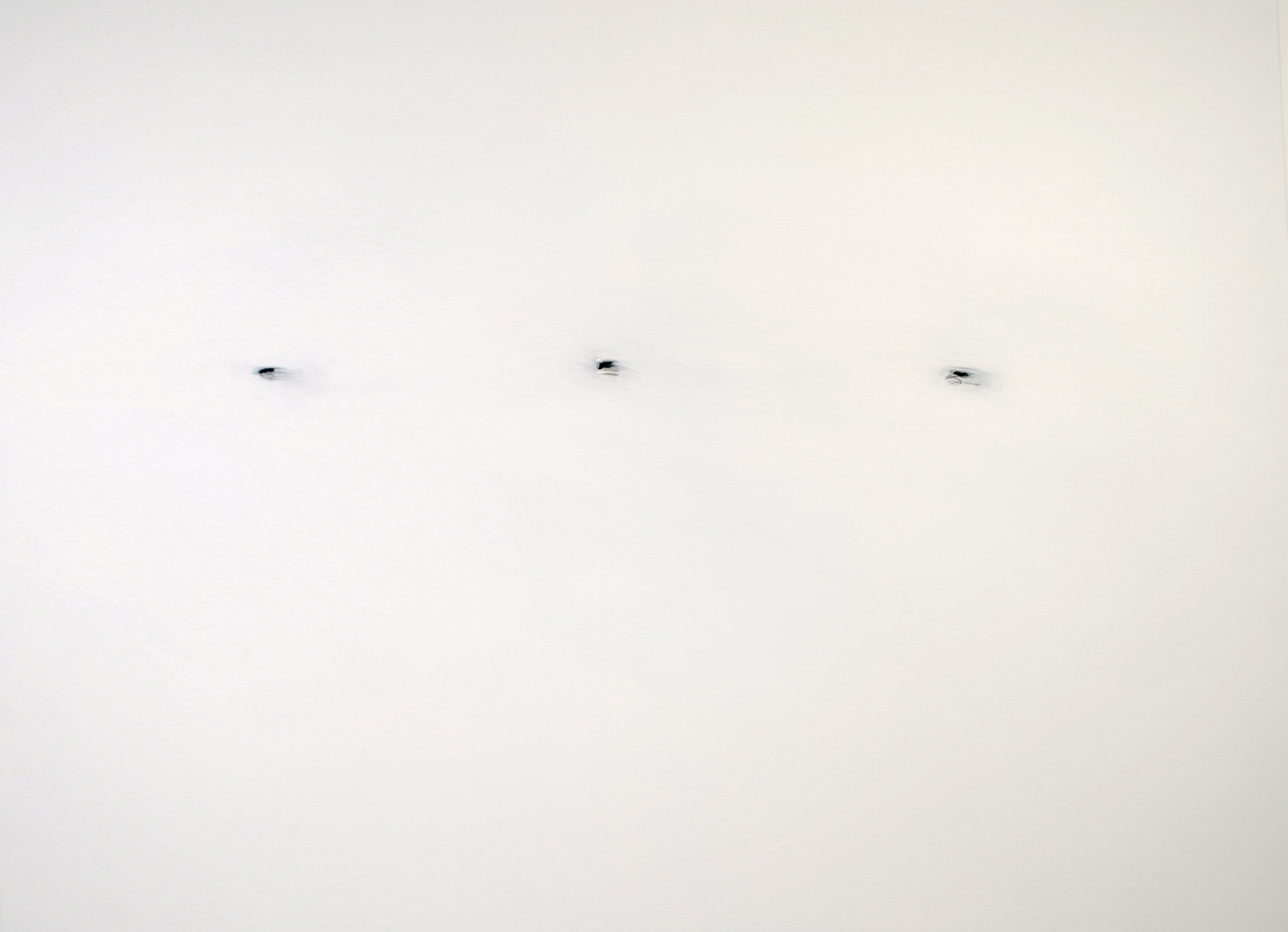

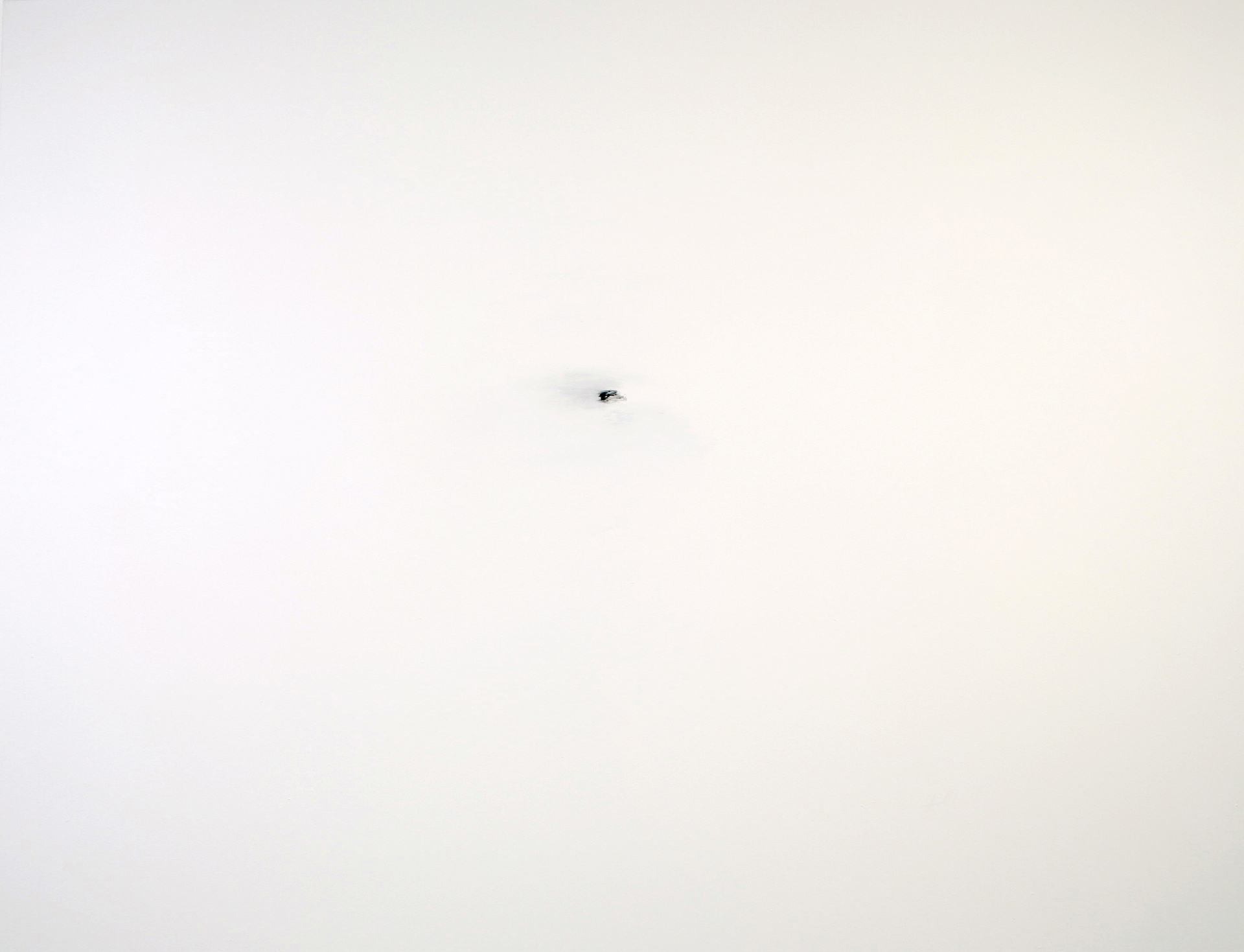

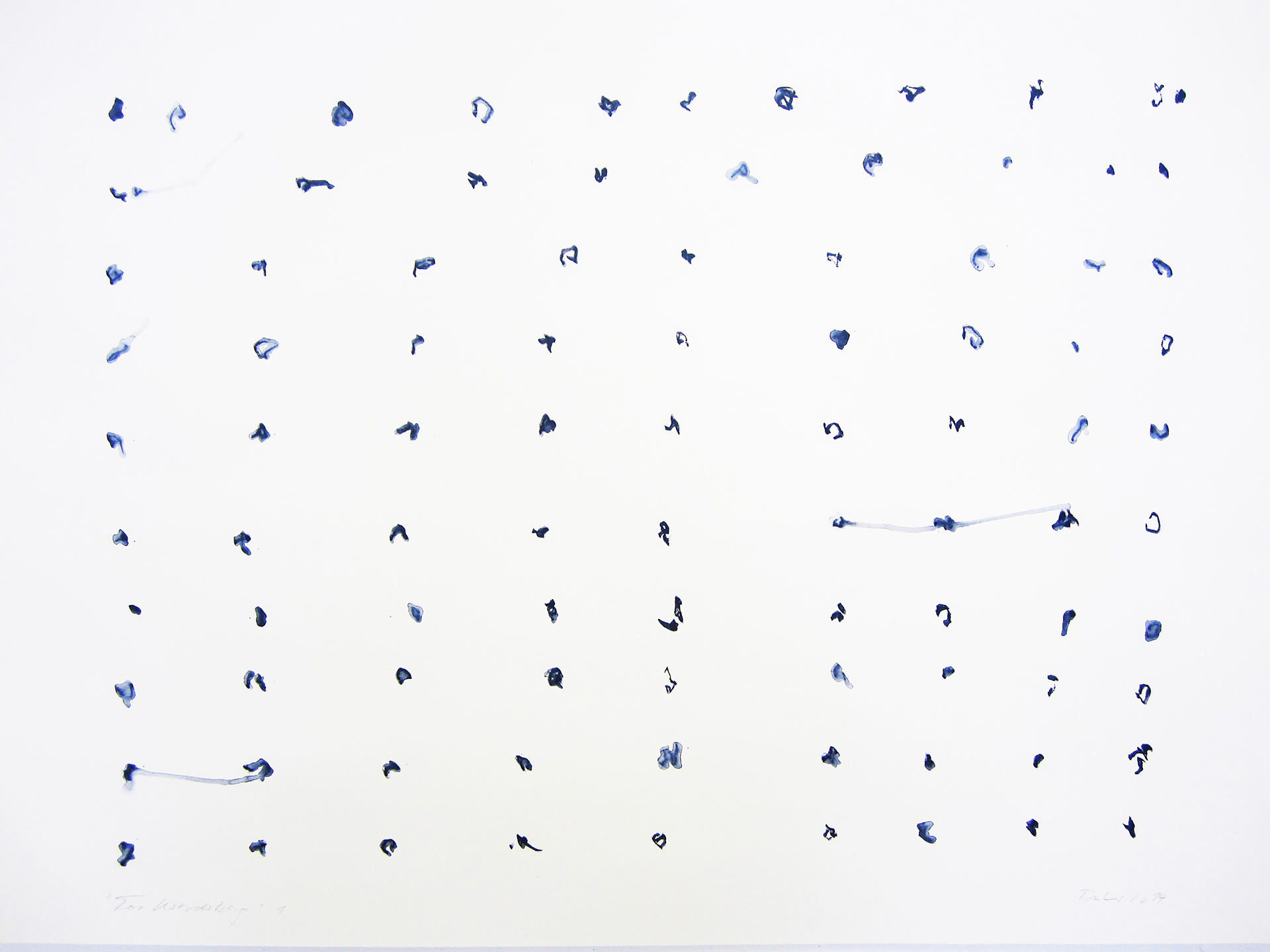

LR: Yes, a very strong relationship. Just by the serial character alone. When I began to empty my paintings, I painted written lines that were not legible; they are also contained in the Kelly letters (Kelly letters: Wolf Wondratschek/Lilo Rinkens, 1988). I continued to flatten this writing until it became a line. That’s when my real research began : away from pure emotion. I no longer set the line as in the Kelly Letters, as an expression of my state of mind. I was interested in the study of the line itself. I deliberately placed the line one by one, in the middle of the large format, I did not touch the edge, no composition should distract, form a horizon or something similar, so that it was only about the line.

HH: Writing also implies a content, then it becomes flatter and flatter until it is only a line and no longer content, why?

LR: There I find myself in the most natural way in the centre of my nature, my being. I became the person who disturbs everything superfluous and in the reduction to the BEING-NOTHING can get closest to the essential.

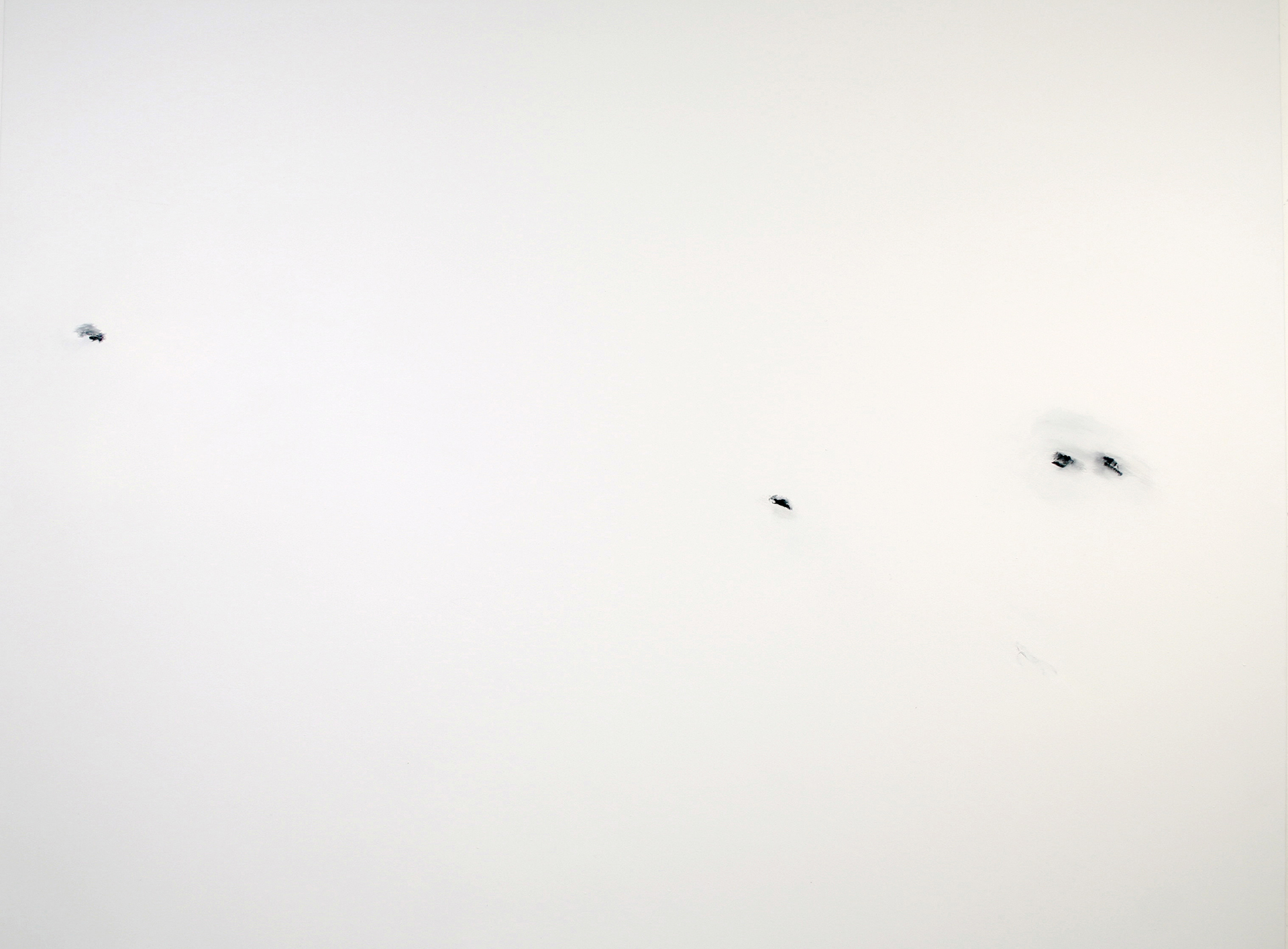

HH: What do you mean that you were no longer interested in how you were doing?

LR: I have left the self-expression. I have become interested in the other: What is it that I see there? What does the Other do? What laws are there in nature? Is what I see on its own, how does it change when it appears together with others? Does it vibrate, is it intellectual, is it restrained, is it searching? I can best formulate this if I leave out as much as possible. If there is only one thing left, e.g. a point, questions arise: does it contain something of everything else? In relation to life: does a human being have everything else in him: is he also a leaf, an atom, a feeling being? As soon as a second point is added, with which the first one forms a certain order, further considerations are added. When I depict series of points, they sometimes seem as if they are in order or perhaps just falling apart. In this respect it also has something to do with time. Time is always implied, even in a single point: there is perhaps a before, is the point immediately gone? Is it getting bigger or are there more? These are investigations, like in science: knowledge through exclusion, variation, working with series, comparing conditions.

HH: Then the point points to the possibilities that are inherent in it?

LR: If there is only one point, then it has a certain vibration in itself, it also has something handwritten, a character – it has a development before or behind it. If the viewer gets involved in it, he can also feel this.

HH: And that then has to do with movement, because it implies movement.

LR: Right. Some points suggest a direction of movement, you might guess where they are going or where they come from.

HH: What phase of work are you in now and what inspires you?

LR: Now it goes from point to fullness. Breathe in – breathe out. I can’t always stay in the extreme austerity and do empty repetitions. But the everlasting silent vision is the barren that is so rich. The point still interests me, it is like an atom, the last element, a cell that contains everything.

Before my current series of paintings I listened to the music of the composer Galina Ivanovna Ustvolskaya; her music is very consistent and strict, of incredible rigor. She inspired me to create this series – it is called ‘Letters for Ustwolskaja’. I am also inspired by the works of people to whom I feel a fraternal bond: be it music, literature, painting.

HH: The severity of the songs is broken by your art.

LR: I believe that this aspect is also contained in the music of Ustvolskaya. The emotion is always there, the imponderables, the small or big catastrophes. I have tried not to put any intentional emotion into it and I have observed its emergence. They contain vibrations of breath, it could not be avoided and I do not want to avoid it, the work of every artist is created from the fact that he is a living being and moves on this earth.

HH: How do the films fit into your work group?

LR: It’s still related to the point : it will always be the main theme; it just can’t be formulated again and again. This farewell was a loss for me: what is there left for me to say afterwards? I photographed a lot to comfort myself because of this loss; from there to filming it was only a small step. I photographed things, places, e.g. a light reflex – places that look as if they were an inner being and that hardly or only very slightly move. When I was cutting, a rhythm emerged that I could influence. The ultimate film would be one in which something moves very finely but you don’t see that it moves or you would have to wait a long time and get closer. Where is the radical limit: is there a film in which nothing moves? If you like: almost all of my works just before the crash, so close to zero. The concentration on the small offer I make to myself makes me more alert. What if almost nothing happens anymore? How do I stand it?

Does a film function completely without drama? If the focal point really doesn’t move anymore, does the film still say what I have to say? I think for me that the border area is the exciting thing.

HH: What role do your drawings play?

LR: My drawings are independent, I often draw while travelling, on paper I can work faster. Paper is more intimate, I work bent over the paper, I am much closer to the paper than the canvas. My drawings are food, food.

HH: The paper or canvas helps to show the condensation, the result of your thoughts.

LR: Yes, I am working and while I am working the error in the question comes to me. The picture then teaches me better.

HH: What was such a ‘wrong’ question?

LR: In my transition from the line to the point I assumed that the line, when it is only a minimum of itself, will become a point, will be even calmer, more withdrawn, withdrawn… I worked on it and I noticed quite quickly that the point has a completely different quality than I thought and has a completely different character: it is aggressive. That’s what the picture told me, so I had the wrong question before. It was theoretical, so I need to work with the painting. Working with the picture helps me to think, not the other way around.

HH: What about without the image material, you just said ‘still’: is your art becoming a performance?

LR: It’s interesting that I said ‘yet’, I didn’t notice that at all. Performance I don’t think so. I sometimes think about whether I want to let art stay, but I can’t. What I experience in the studio I can only experience by doing it. It is my way to get spiritual nourishment or to become clear about feelings and to reach insights.

HH: What role does Munich play in your art?

LR: If I am honest, Munich doesn’t play a role. It plays the role that it leaves me in peace, that I can work in peace. I am not looking for the scene. I’m not looking for contact with other artists, though that may be a flaw, but I tend to be a loner.

HH: I think that your partnership with Wolf Wondratschek gives you an intensive exchange.

LR: That’s true; we sit together all the time and talk. Since we are very different, also in temperament, but respecting each other’s work, it works very well. Perhaps better, because he is a writer. The artistic questions are similar, but the solutions are sought in different media. Wondratschek knows my work very well, he sees whether a work is strong or weak and is usually right about that’ – that is the ‘foreign’ view when I am entangled by too much proximity to my own work. In this way I naturally get an exchange and the world outside by and large does not.

HH: Mrs. Rinkens, thank you very much for the interview.

_________________________________________________________