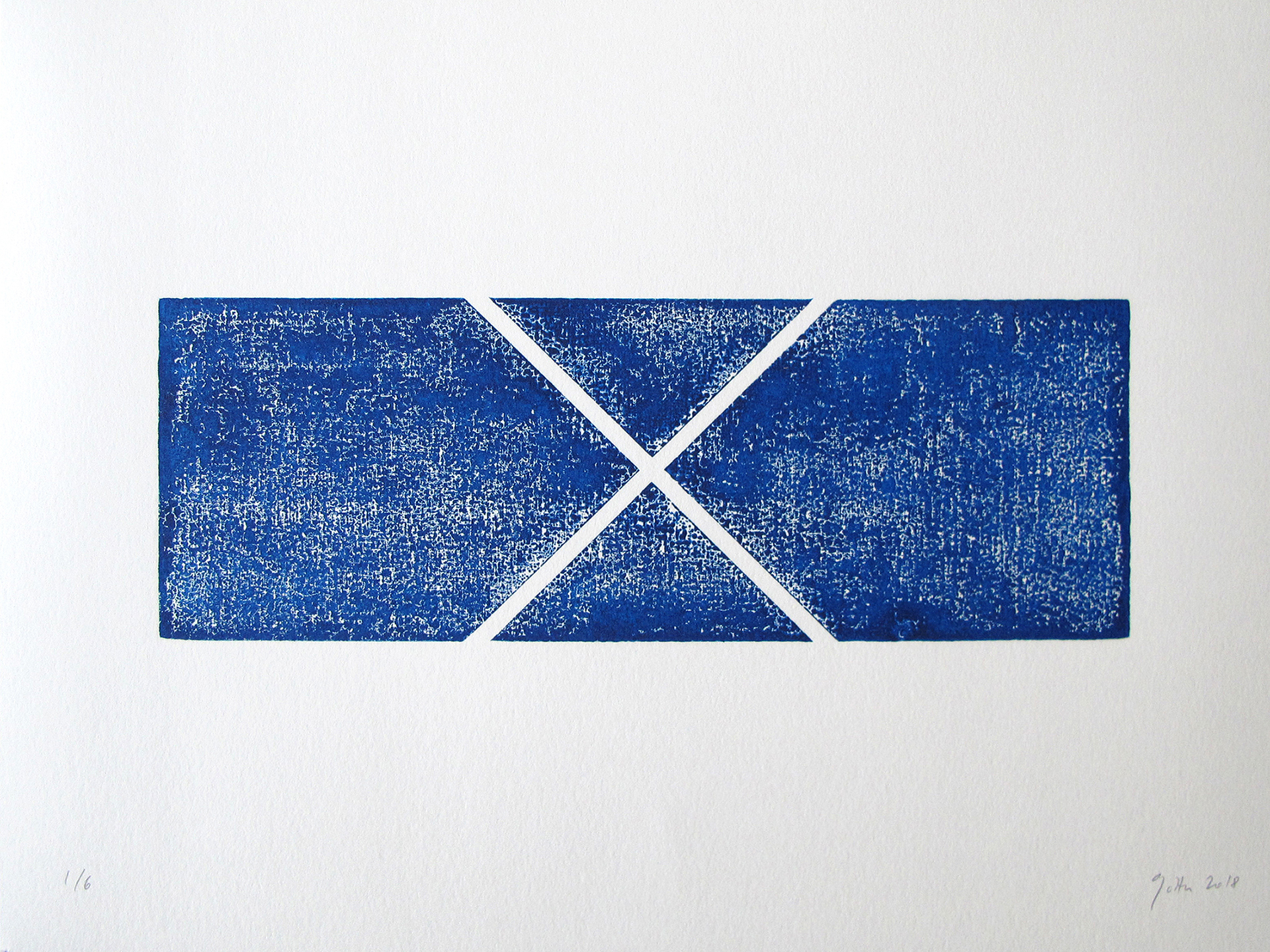

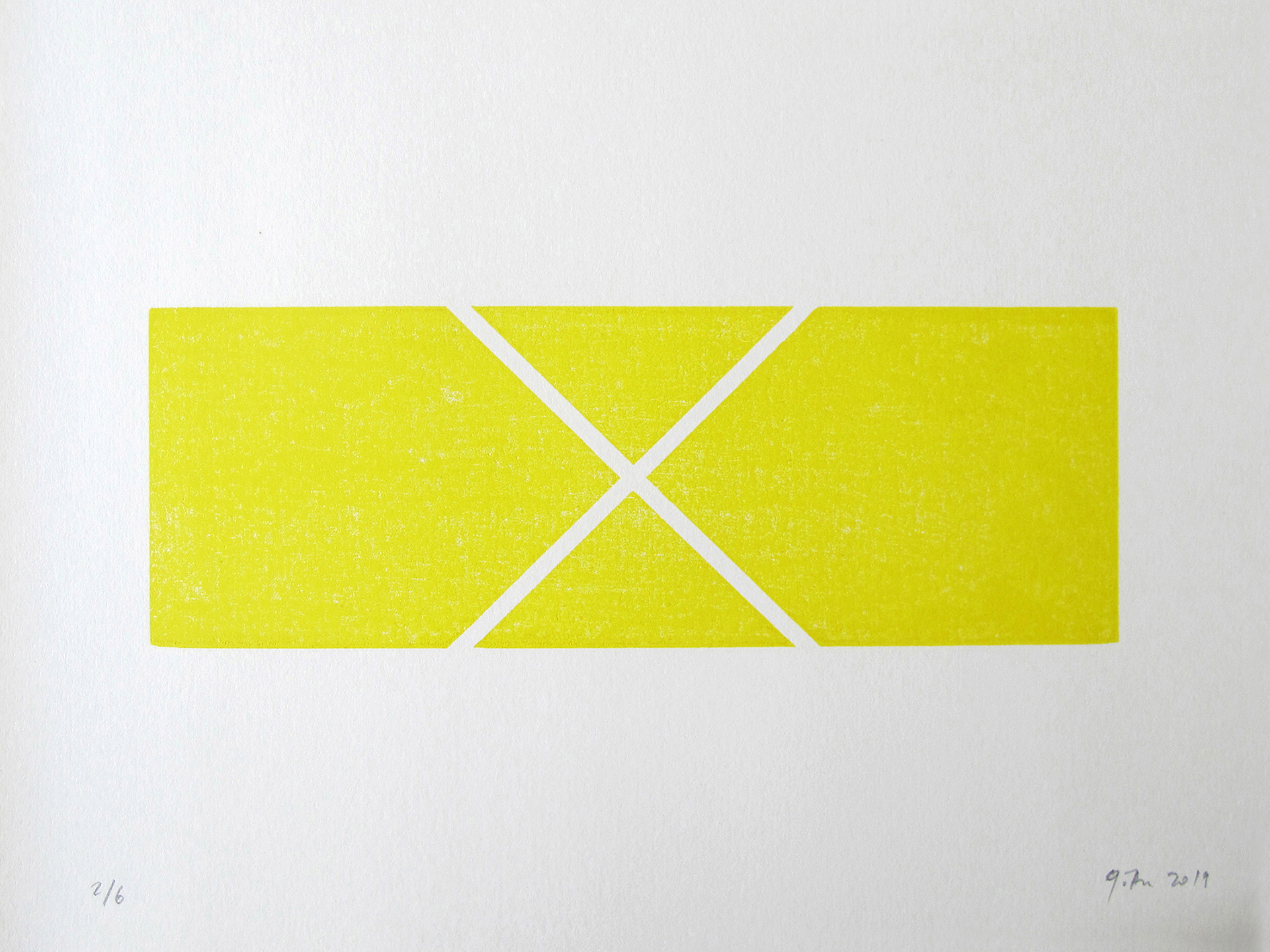

Kunstforum Edition 253, 2018, Drawing at a time, p. 190

Daniel Goettin

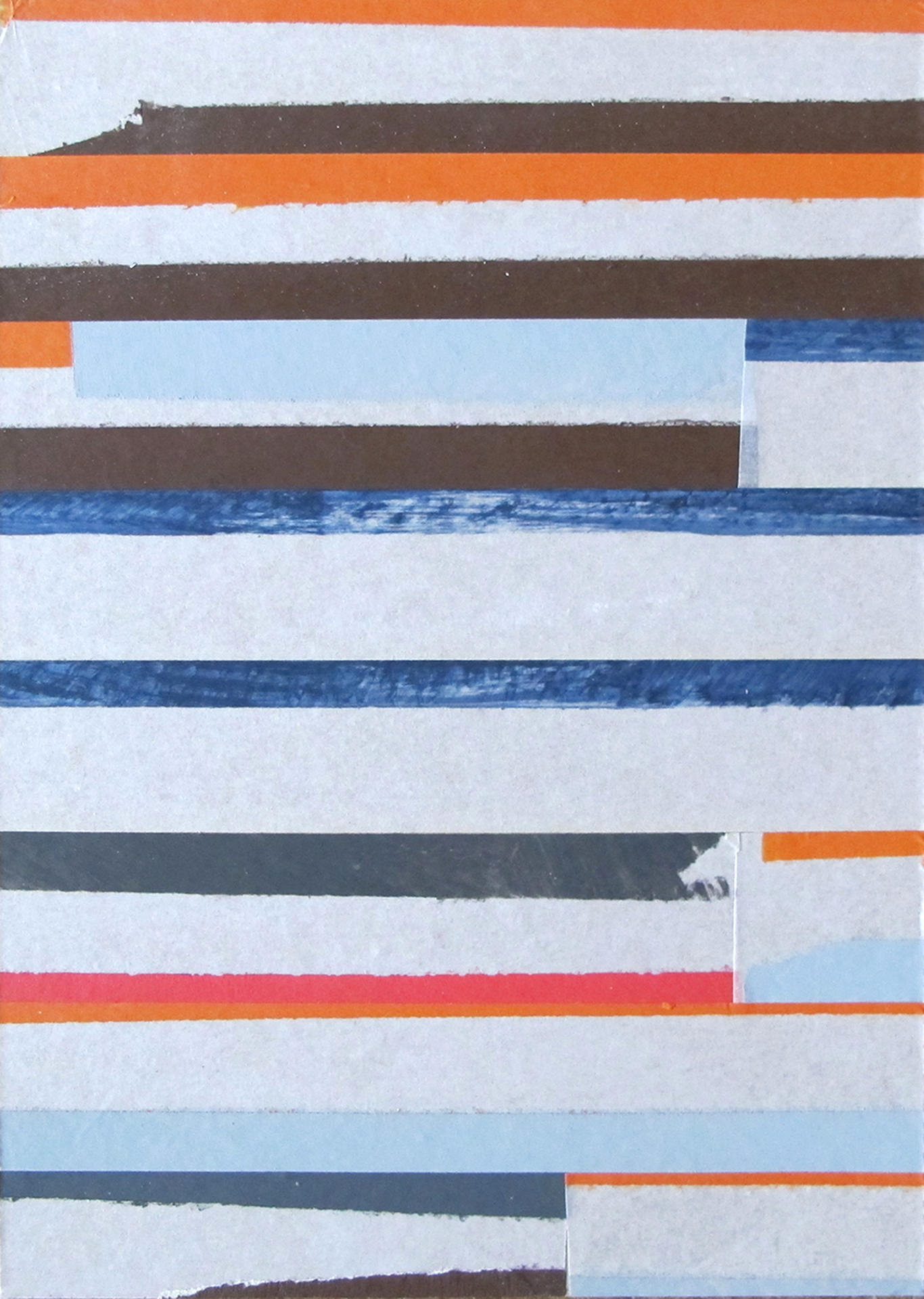

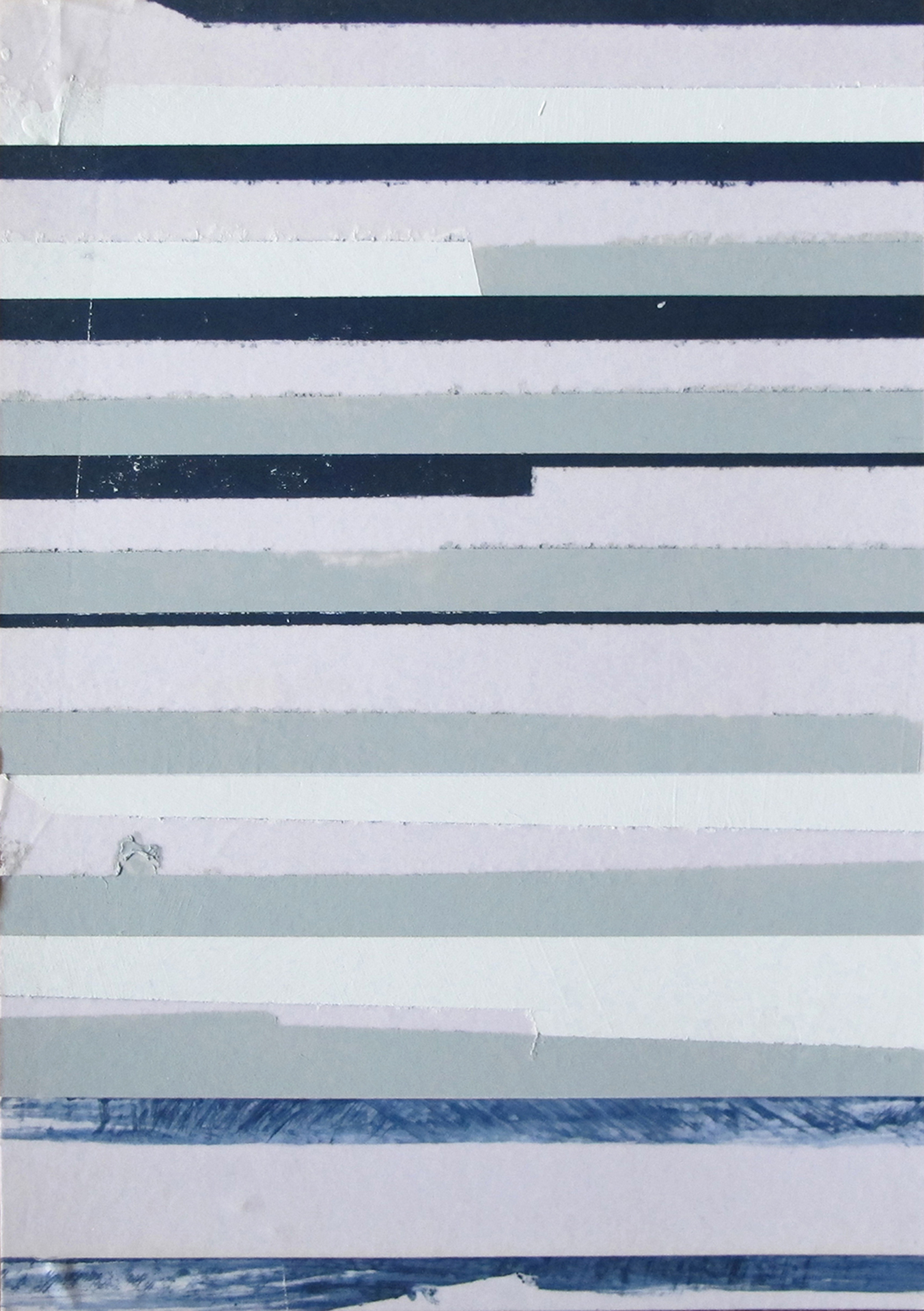

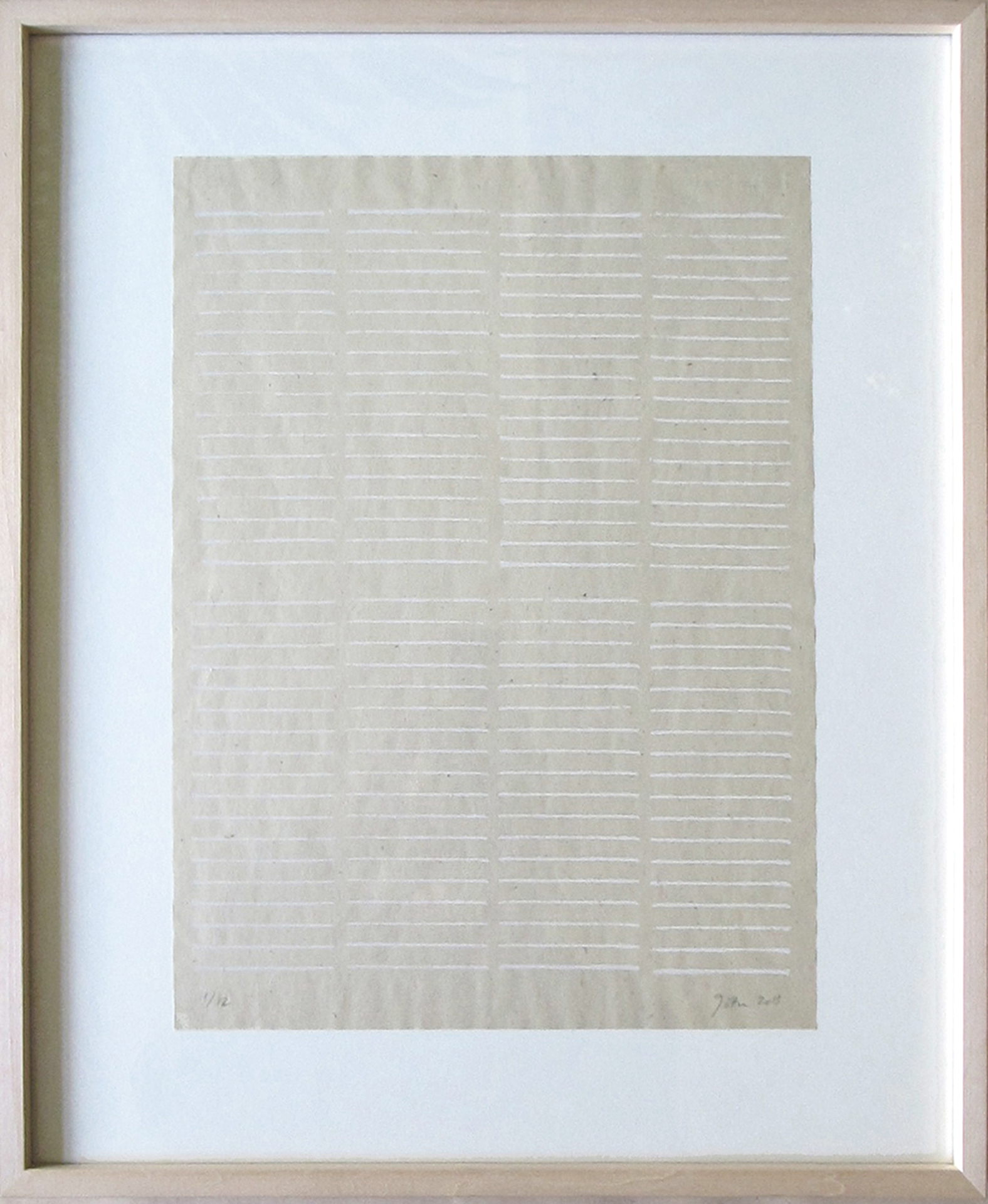

Daniel Göttin draws with adhesive tape. With an English vocabulary you can immediately create a medial matter of course: Tapedrawing. The tape does, occasionally one could also say, it ‘paints’ the lines. This drawing takes place primarily in space, this is an installative art that does not impose itself, however, sometimes it is not even visible at first glance, the lines have found themselves in situ, as an accentuation of space and depth. This results in “approximations” or “frames”, whereby Goddess likes to lead the tape along given wall projections, constructive ribs or simply along the architectural pivots. Then the underlining of the given or built becomes an illustration of proportional deficiencies, which is somehow also repaired by the linear intervention; temporarily, because the installative intervention is often enough temporary. “Space as space is at the centre”, says Konrad Tobler. In spite of the absoluteness associated with this assessment, a fine line between applied and free art appears to be a tense moment. Goddess sometimes creates free, but ultimately defined surfaces on the walls at his disposal, which then play upon others. He makes allocations, indeed he creates displays, in order to use a modern everyday concept. Does he govern the room or does he react to the room? The place of such an allocation, filled with only a few strokes of the pen, simultaneously gives itself self-confidently autonomous. “There must be an easy way,” says Fred Sandback in conversation with Daniel Göttin shortly before his death. The American thus also meets a core idea of the Swiss. It’s all about undisguised, essential solutions with high intrinsic value. And: The simple is beautiful! His linear interventions have what it takes to create independent wall drawings that appear as strong images, with graceful divisions in dialogue with the speaking proportions, which are usually not calculated, but always feel, if you like, intuitively drawn.

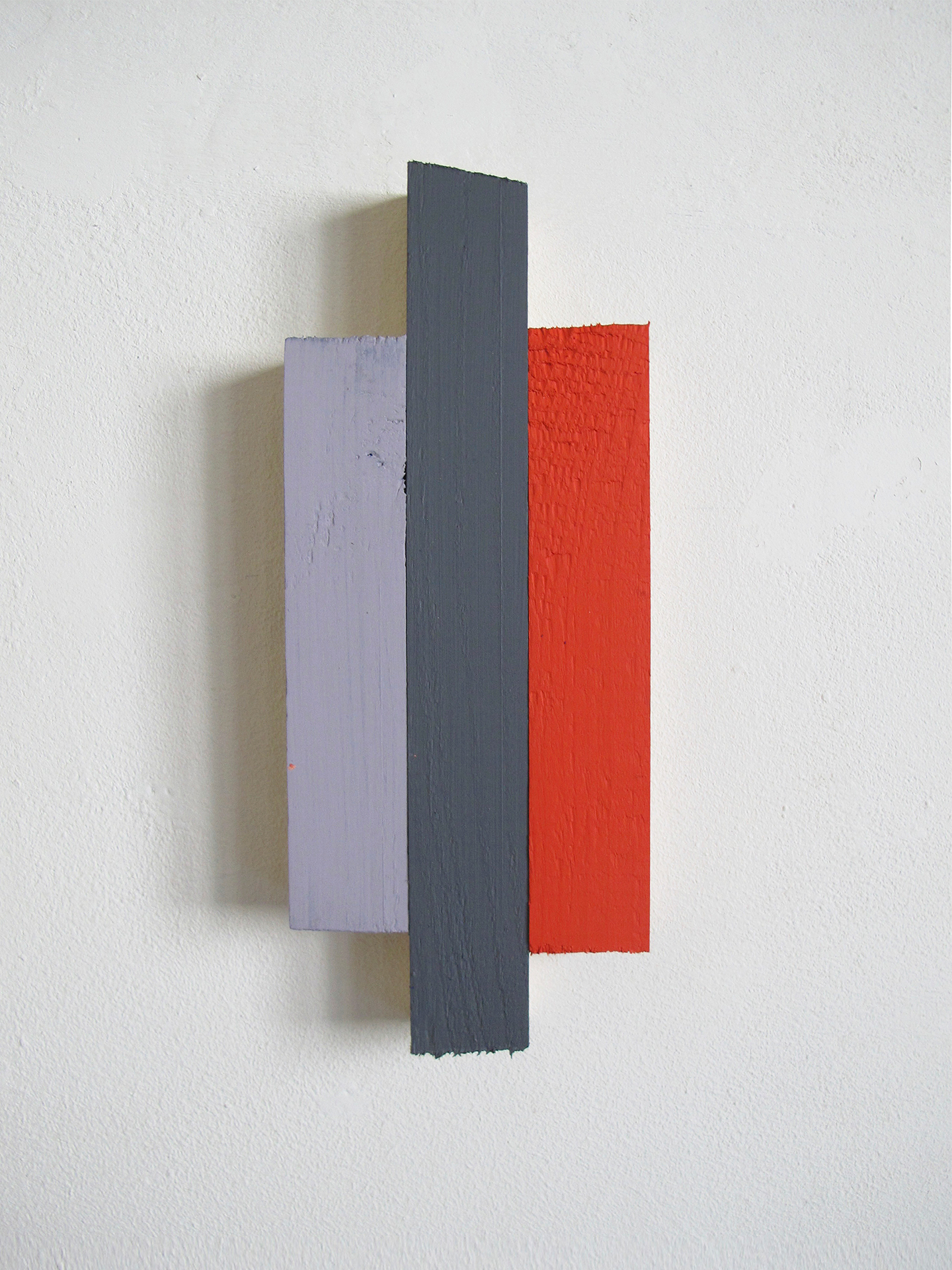

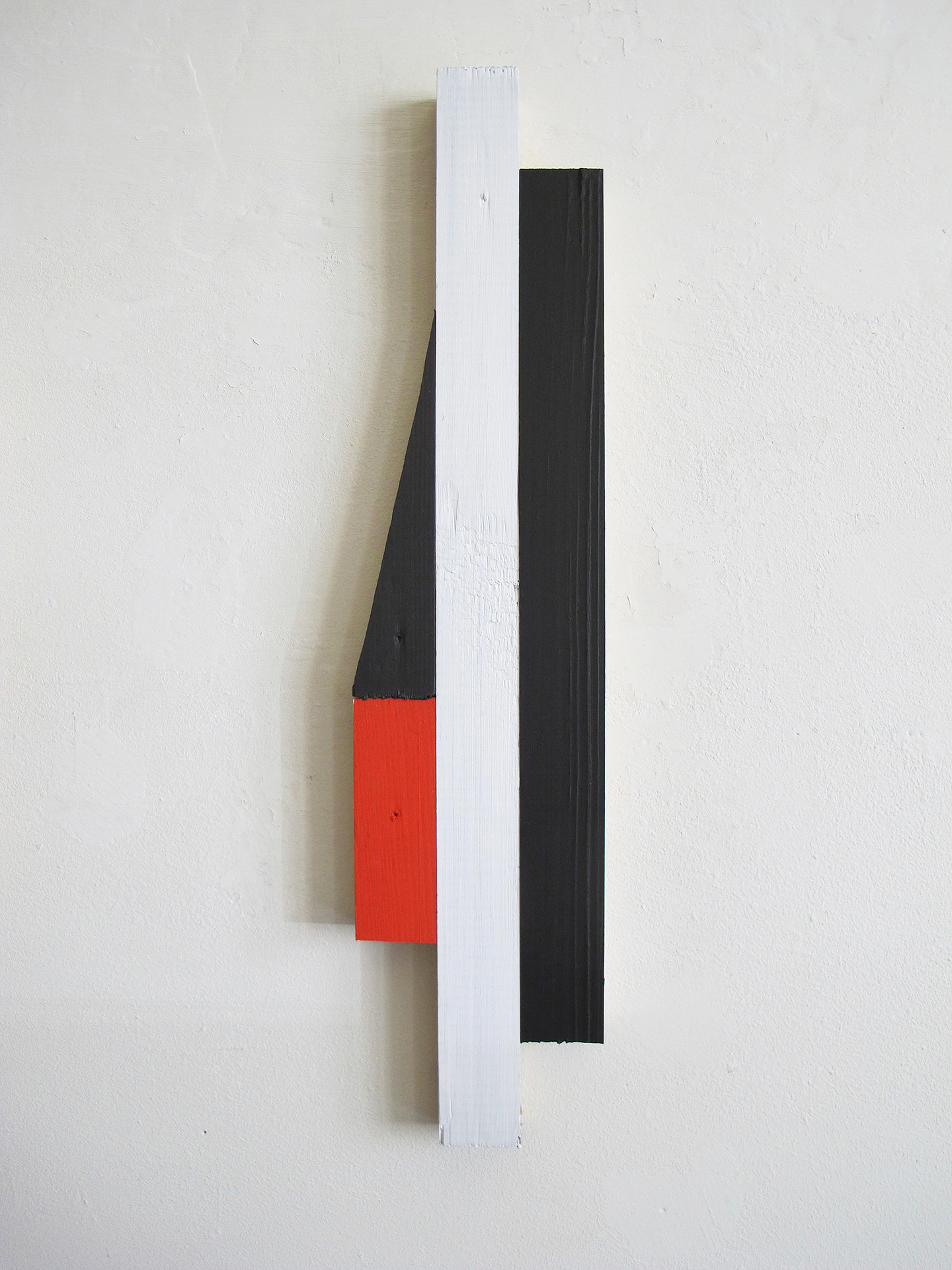

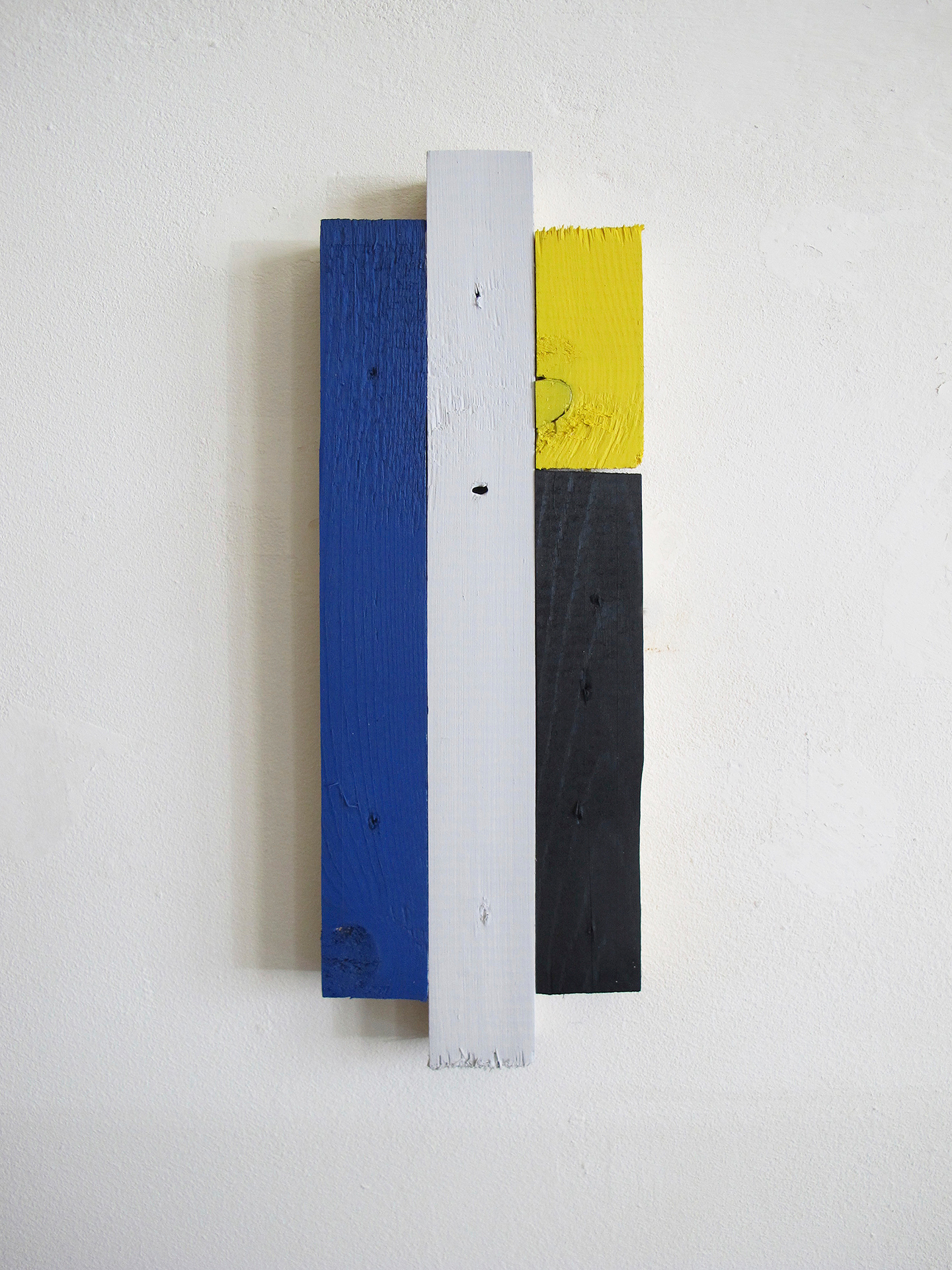

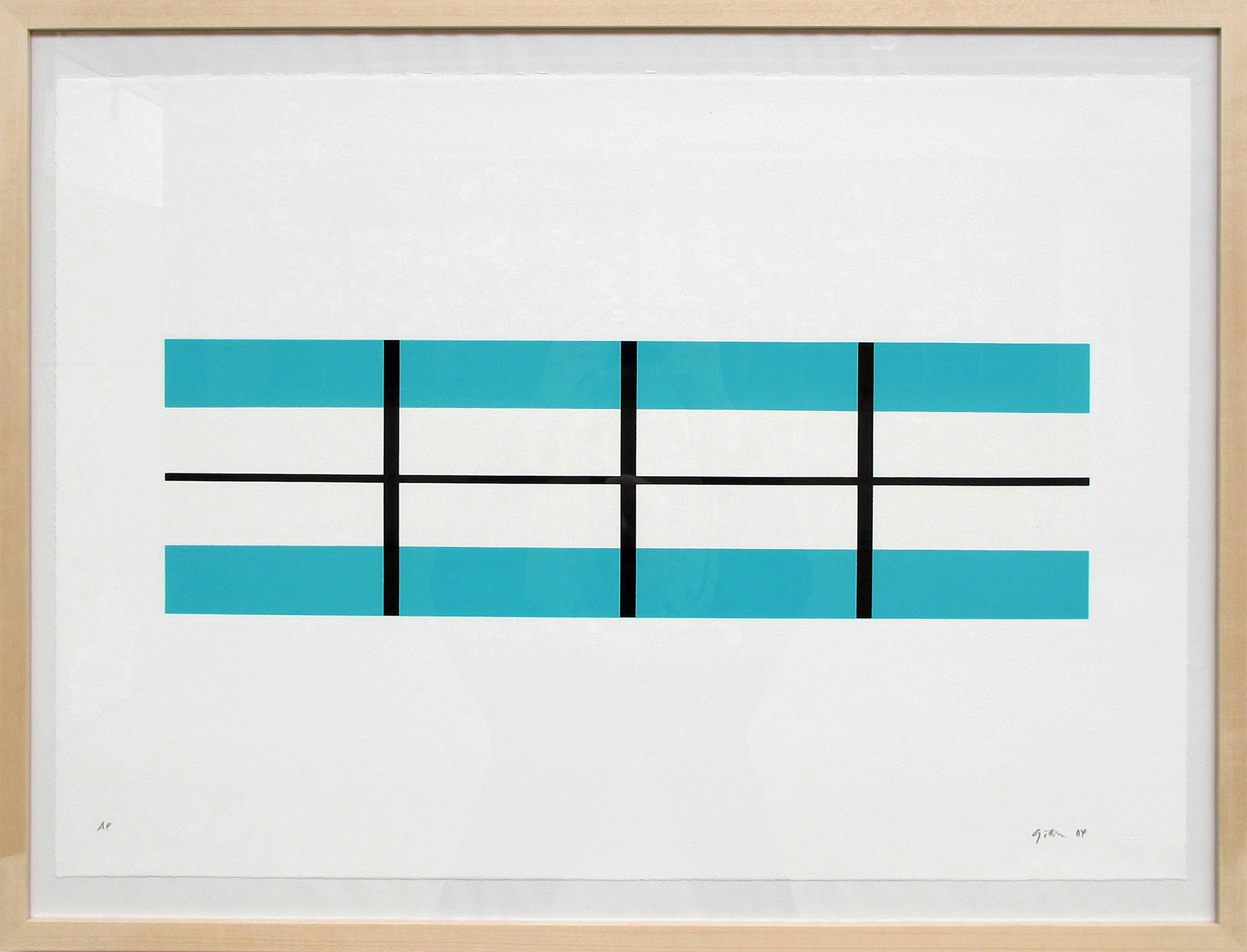

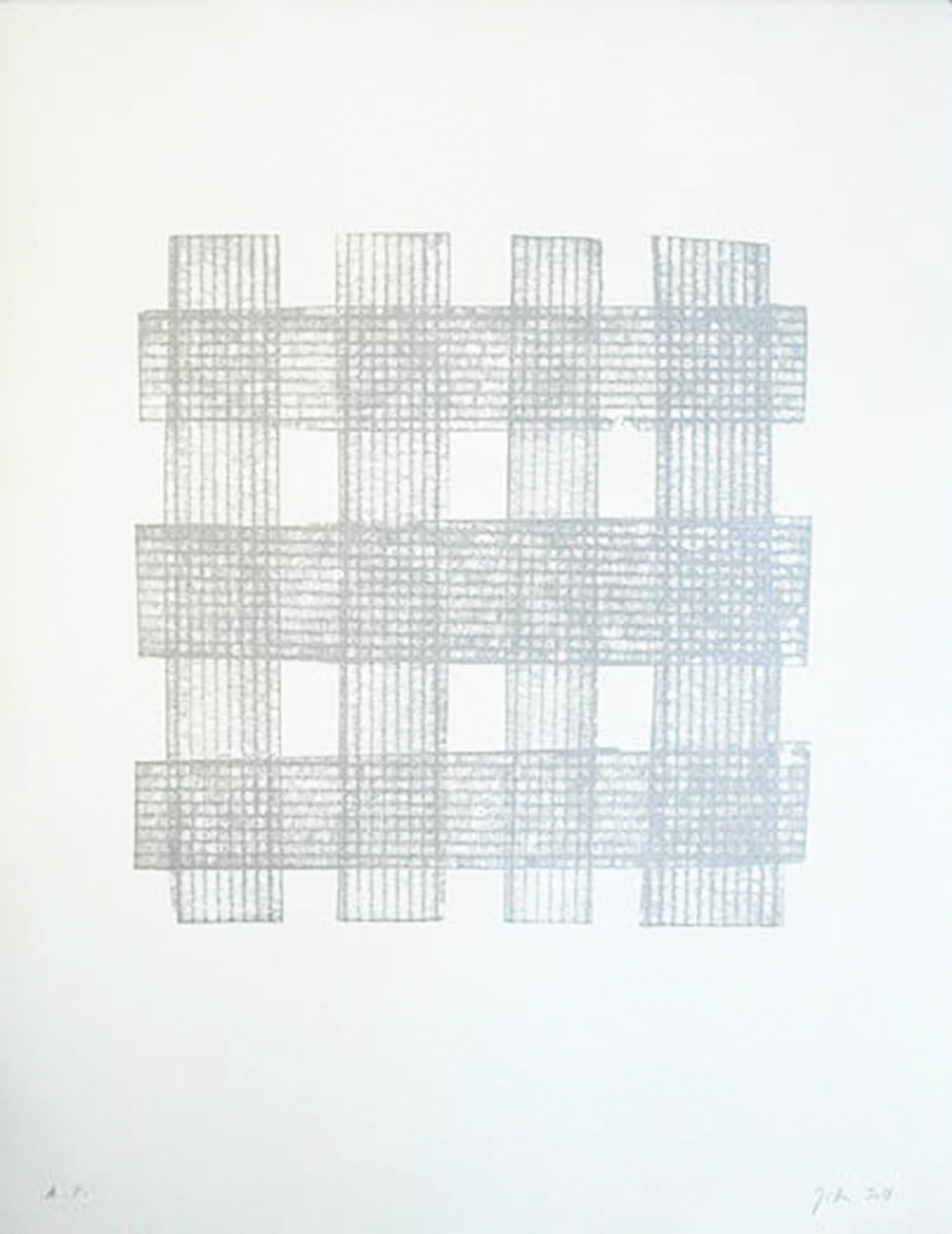

In addition to the orthogonal works that have occupied him since his late years at the academy, since 2000 there have been the Networks, linear network structures of squares and pentagons that grow as freely and crookedly as they appear. There are also hexagonal intermediate links. A spacious craquelé can be seen, which fills walls and entire rooms, while at the same time respectfully following architectural and artist’s specifications. The occasional technical-mathematical impression, which can also provide the viewer with a feeling of self-evidence, is deceptive. He needs the computer primarily to document his work. Of course, an innate precision prevails. The fact that Göttin enjoyed training as a technical draftsman before studying art is certainly noticeable. These structures grow from a chosen beginning, they are written in space. “First this, then this, then that,” says Daniel Göttin. No field is like the other, there is no repeat, no line runs through it, at each node there is a change of direction, no matter how small. In addition, Goddess sometimes backs these organic structures with parallel nets running in opposite directions, with parallel nets of different colours, he reinforces the basic structure or he cuts through the cells with extensive grids. These networks, of which there are now 58, have developed over time into a kind of laboratory for the artist’s repertoire of forms. A repeatedly varied cross object owes its existence to the nodal points of the networks; three-dimensional bodies develop from the irregular fields, which sometimes even protrude from the wall drawings. The sculptor is partially a product of these nets and vice versa. Part of the concretion of this work is the use of colour, Goddess does not only paint with adhesive tape, but time and again in the traditional sense. In addition, he likes to work with fragments of lawn carpets, which also set ironic accents as violent pieces of colour (not only in green).

Tapes in all possible appearances define and structure the handwriting of Daniel Göttin and his straight and crooked paths. In addition to the preferred textile and aluminium tapes, he often uses 5 cm wide transparent adhesive tapes, which he stretches into the open space, guided orthogonally by the given orientation and holding points. These are energetic, also sensitive, but ultimately independent architectural additions that depend on a carefully exploring audience. If one wanted to speak of drawing in this particular case, one could speak of air lines that realize their precise divisions like light shadows.

_______________________________

Interview with Daniel Göttin by Chris Ashley

posted March 1st, 2006 on MINUS SPACE, Brooklyn, New York (www.minusspace.com)

Introduction

It seems somehow appropriate to me that Daniel Göttin’s recent wall works—those in which lines of tape placed on a wall are used to make a large, dense web of intersecting lines—are called Networks. Over a two-month period Daniel and I talked about his art via electronic messages relayed back and forth across a complex network of thousands of miles of cable between Basel, Switzerland and Northern California. He could write to me in the evening, and I would receive his message moments later in the morning, a kind of time travel. My job was easier than Daniel’s—we wrote to each other in my native English, rather than his native German, and I got to ask all of the questions, then sit back and wait for his reply.

As we sent questions and answers back and forth, and also exchanged pleasantries and observations, our conversation began by meandering from point to point, gradually establishing different nodes of reference. Over time an order was recognized, and the conversation was eventually shaped and contained within the boundaries of the interview format. In doing this we responded to a situation and found a form within it. Similarly, I recall how in our discussion Daniel described his process when making site-specific works, and it occurs to me that his work is also a conversation, but one that takes place with materials and spaces that involve time, various distant locations, perhaps negotiations with bureaucracies, and a flexible and open language.

Just as how in our interview Daniel speaks with extreme clarity and thoughtfulness, his art also possesses these qualities. But this clarity is not the result of a fixed or repetitive position or strategy. Instead, his art is iterative, responding to changing conditions and environments. Different aspects of his work, both the works made on the wall and the objects made for the wall, are inter-related and work off of and reflect on each other. There is a wholeness to what Daniel refers to as an entity—his body of work.

Chris Ashley

February 2006

The following conversation between Daniel Göttin and Chris Ashley was conducted via email in English between December 2005 and February 2006.

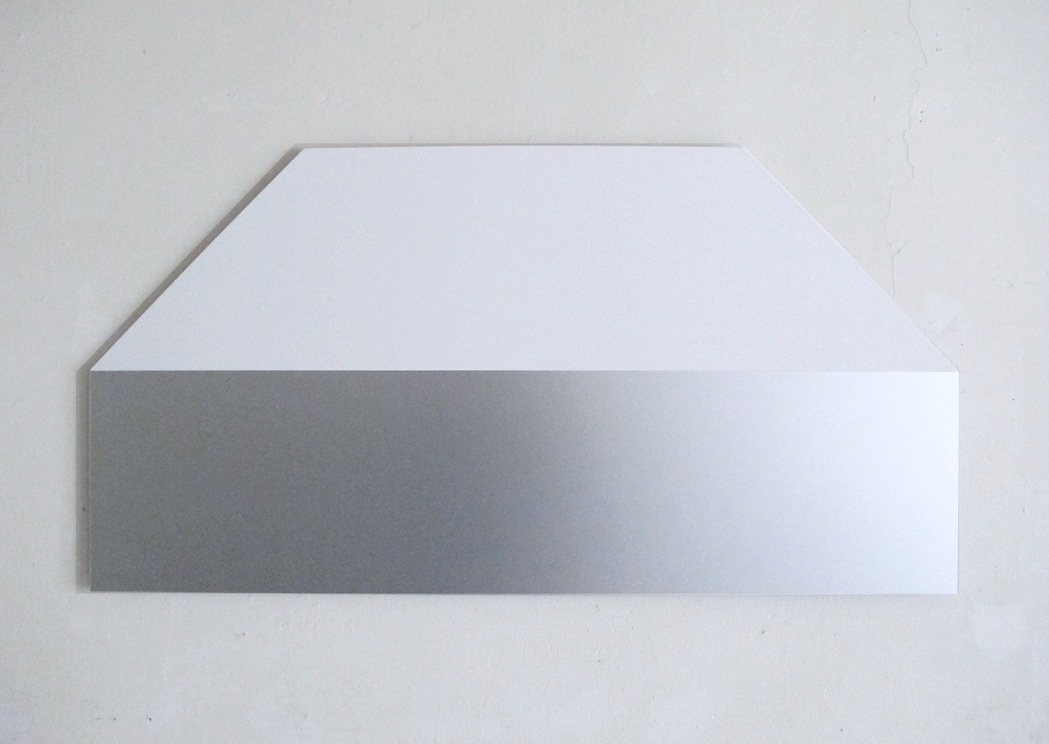

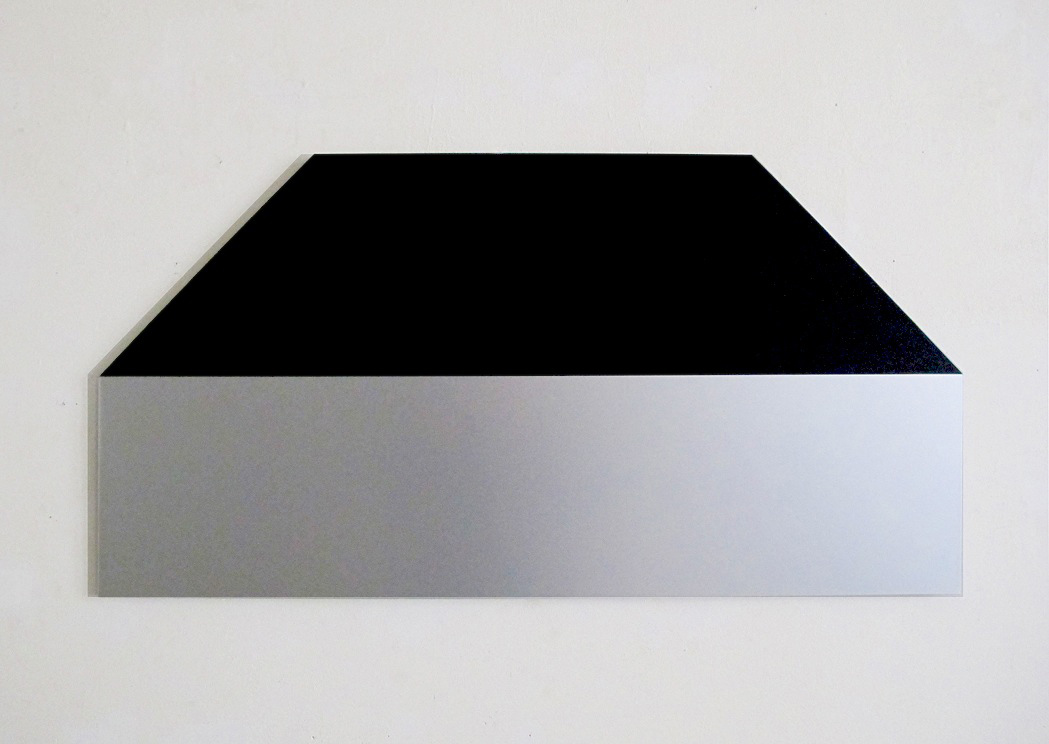

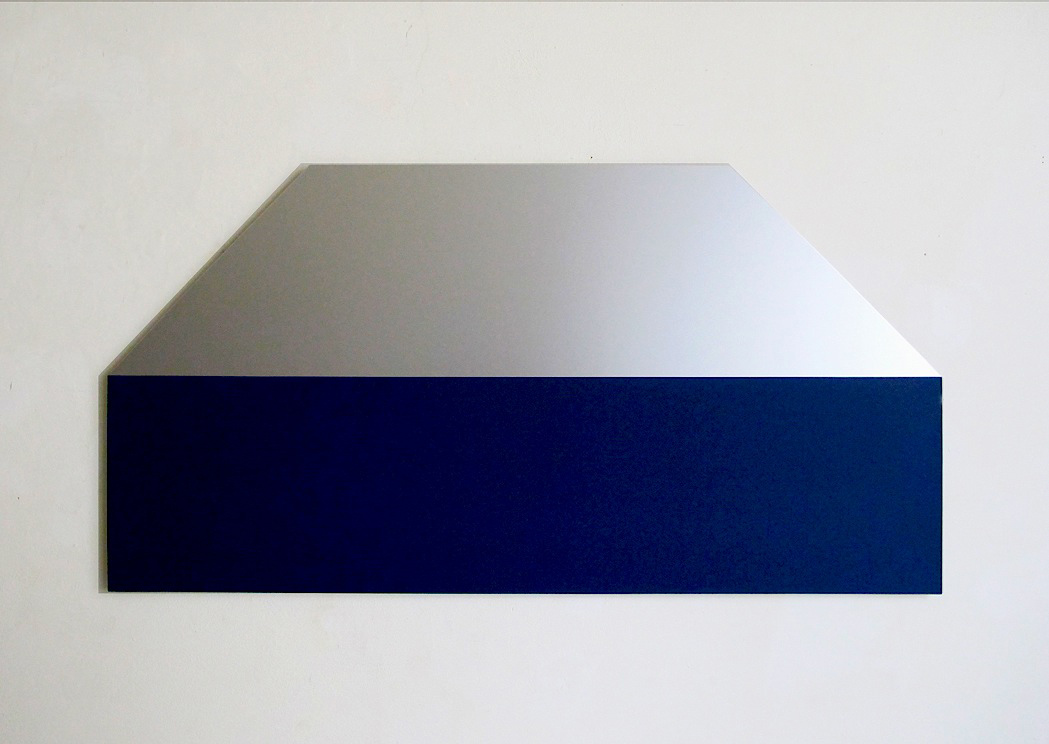

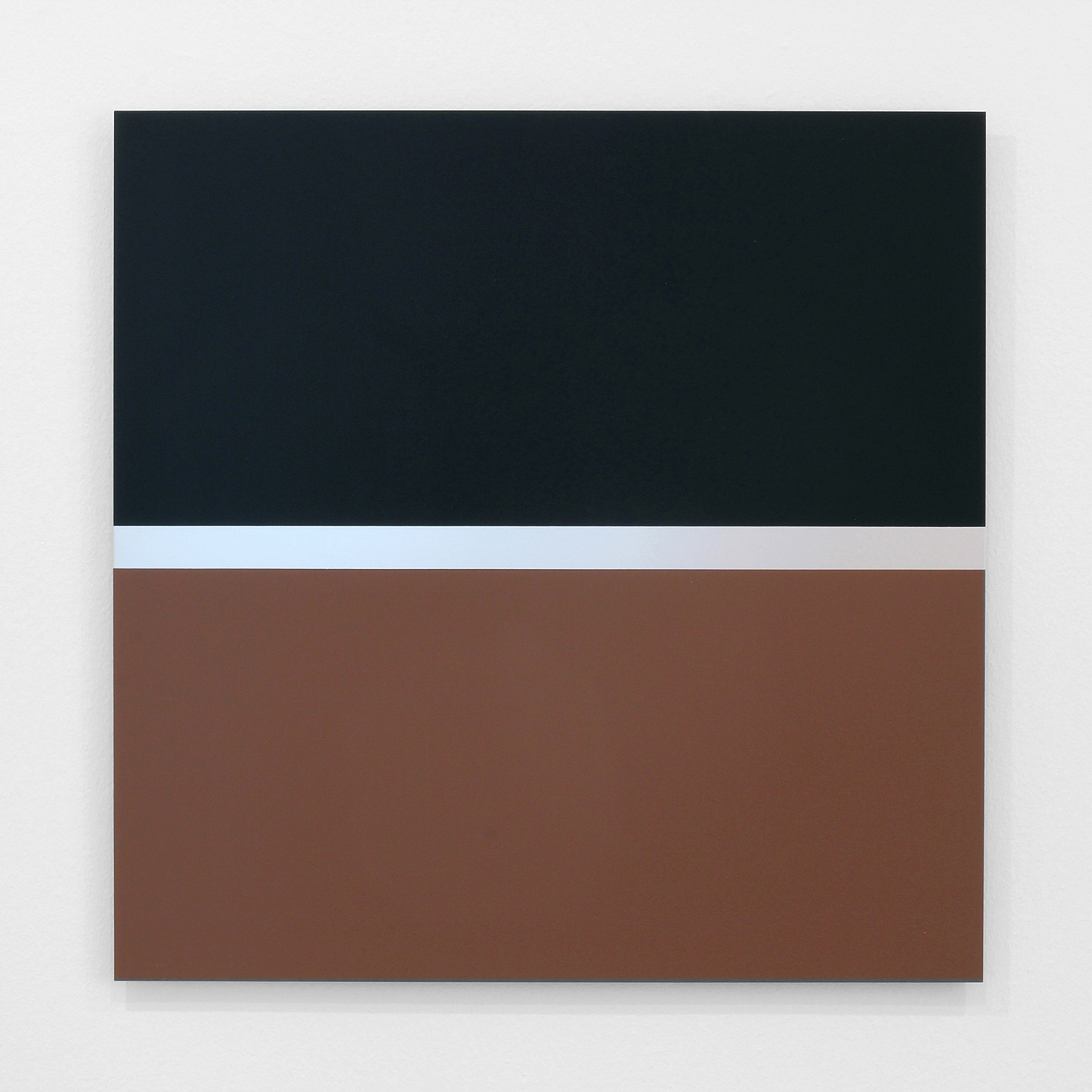

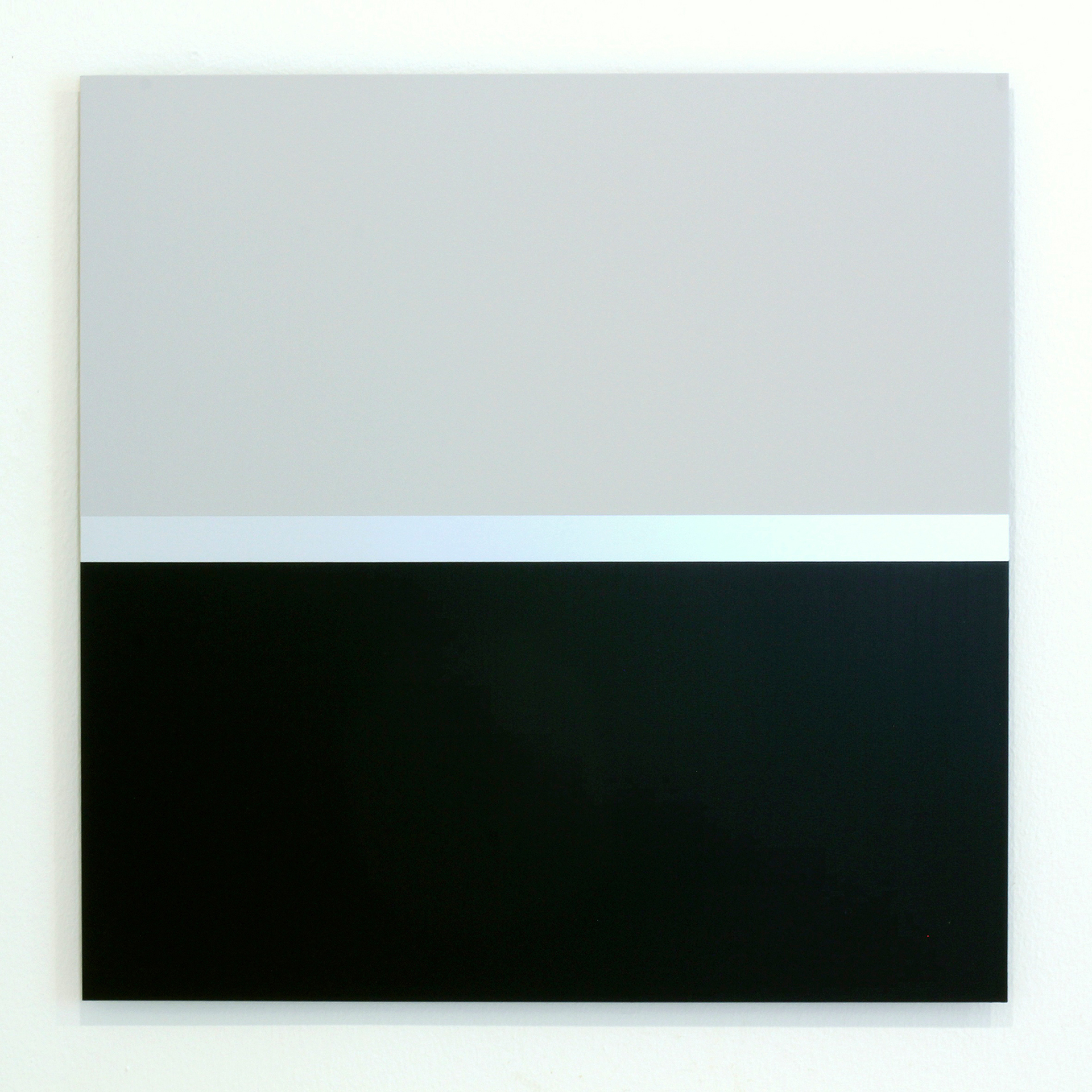

CA: Daniel, your work can be roughly divided into two groups: site specific work and colored or painted objects for walls. The site specific works for interior walls are typically made with paint and tape, and you make works for exterior walls, too. You also make painted objects for the wall out of aluminium or MDF, and sometimes free-standing objects. Can you talk about the difference between these two kinds of art?

DG: The difference between these two kinds of art is a difference of location and condition. The starting-point for a site specific work is the space with its specific qualities where the work will be installed. I use the given information (for example, plans, photos, sketches) to create a work that co-exists with the space. It is a collaboration between the given, already existing part of the site and the new part I add to the site. The idea is to combine the already existing with the new into an entity in time and space. The work only exists in and simultaneously with the space, and both become active parts of the art work having equal rights. It is not possible to move one of them to another place—its existence is unique. The works made of aluminium, MDF and other materials are works I produce either in the studio or I let them (or parts of them) be produced in a factory. In many cases it is again collaboration, this time with the factory worker. This changes the conditions. I don’t need a site but the studio to make the work, and the number and sizes of the works are limited. The works made in the studio don’t depend on a specific site, but on the conditions of technical possibilities of production. They are movable, and they can be shown in different places. Since I am switching between the two kinds of art mentioned, they are still parts of a broader entity.

CA: How would you define this broader entity, which I assume is your overall concern (or concerns) as an artist under which all your work falls?

DG: The broader entity is the view of the world in general. Art is one aspect besides many others. It is about art and life. It is not so much about art itself as one entity and life as another entity, seen besides each other. It is, rather, a permanent mutual influence. Art can be a way of living, and life can be artistic. Art is not necessarily only painting (like most people think), or sculpture, or something else in the field of art. To me it can be anything I see or define as art. It is a free field without boundaries. It is about the conciousness of how someone perceives something: the world; the far; the near; the broad; the detail.

Usually art happens in the context of a gallery, a museum, or in places pre-defined for art. In these places the work shown is defined as art because of the context. It can also be challenging making art in a place which is not defined for art. Then art plays on the same level as anything else; it connects with life.

CA: Besides showing in Europe you have also shown quite a bit in Japan and Australia. How have those opportunities come about?

DG: These opportunities came about through the universal language of art as I understand it: Also, as a two-way-system communicating between two equal parts, the existing and the new, the known and the unknown, the seen and the not seen.

CA: Do you find that working in different locations—different cities and counries—greatly affects the work that you produce there? Of course, you find various materials in different places, so there is that affect, but I wonder if there are other influences that are specific to the location in which you’re working, for example, language, light, geography, pace of life, etc. How do these affect a work that you produce on-site?

DG: Installing and producing in different locations certainly has an affect on my work. Sometimes I consciously include aspects of the local situation into my work, and sometimes I only realize the influence later. Thinking and working is about connecting and relating to the site where a work is made or installed. Being aware of the location or the site is part of the concept.

For example, in Australia the light is so incredibly intense that it changes the color range of some of my works. In Marfa, the presence of Donald Judd’s work and some of his artist friends’ work is so strong, and so sensitively, precisely and carefully installed in the context of the natural environment and everyday life, that it sharpens the perception and the conciousness of how to work with material, proportion and space. In Japan, the visual and architectural language had some effect on a concept for a tape work I executed there. The work turned out to be a European-Japanese combination. My artist residency in New York last year was different again. On the one hand, there was living and working on the edge of Soho and Chinatown, between East and West, in this fast, big business, art metropolis. On the other hand, the experience of all the waste, and all the low budget projects, made me work in a more improvised way, with leftover cardboard, for example, and even taking up photography.

Since one location is remote and quiet, and the other is busy, fast and loud, different locations have different effects on my work. A beautiful landscape, a vast night sky, the incredible ocean, friendly people, interesting discussions, great art, cultural offerings, a good restaurant, a nice bar, a fun time— everything is part of the experience. All of these specific qualities in different conditions and in each location is a challenge for new work. I adapt my concepts and myself to the new situation. My cultural background connects with the background of the new location. This is what makes a site specific art work possible.

CA: In an interview around the time of your Chinati residency you said, “I use normal materials. They’re not expensive.” You also said, “I don’t do things that anyone else couldn’t do; but I DO them.” If these words were taken out of context it might make your work sound somewhat ordinary or simplistic, which it isn’t. An important distinction between doing and not doing something creative or meaningful is actually “doing” it—taking action How did you arrive at using the materials you use, and how do you go about making a site specific work? You have referred to making “interventions“, and I would assume that time—or, perhaps, the time given to make a work— is a factor in how a work comes about.

DG: The Chinati residency was a good opportunity to use everyday material, since there was no other (art) material to get at that time in remote Marfa. I made a site specific work from material I could find in town, again working with the given conditions. I got white cardboard boxes (with no printing on them) from the post office down the road, and some clear adhesive tape from a small supermarket called Wynn’s at that time. Since the Southern Pacific Railroad impressively divided the small town in front of my studio every day, it made sense to me to include rocks from beside the railroad tracks for the work. All these materials were within a mile’s distance—I just brought them back for a temporary artwork. Normal, everyday material means material that is only valid in its usual context. And doing means to materialize an idea, to make it exist in the real world. An artist residency gives me the chance to spend some time in a foreign place. It is interesting and challenging to visit a new place and find out what I can do without having a plan. Everything is new: the people I meet; the location; the way of living and the way of making art. I use the time I spend in a new place for creating a work that is related to the whole situation and its conditions. This is the source, a point-zero combined with my previous experience. The conditions can have a strong influence on the work, as well as on life. This leads to a way of working that enables me to make art work in any situation. I would like to make art works of any size, of any material, in any place. Conditions can be, for example, time, location, space, materials, language, impressions, and money.

CA: What are the criteria by which you can determine that a temporary, site-specific work produced under these conditions (newness, foreignness, time limits) is successful? Can you give an example of a wall work that you thought was particularly successful, and explain why it was successful?

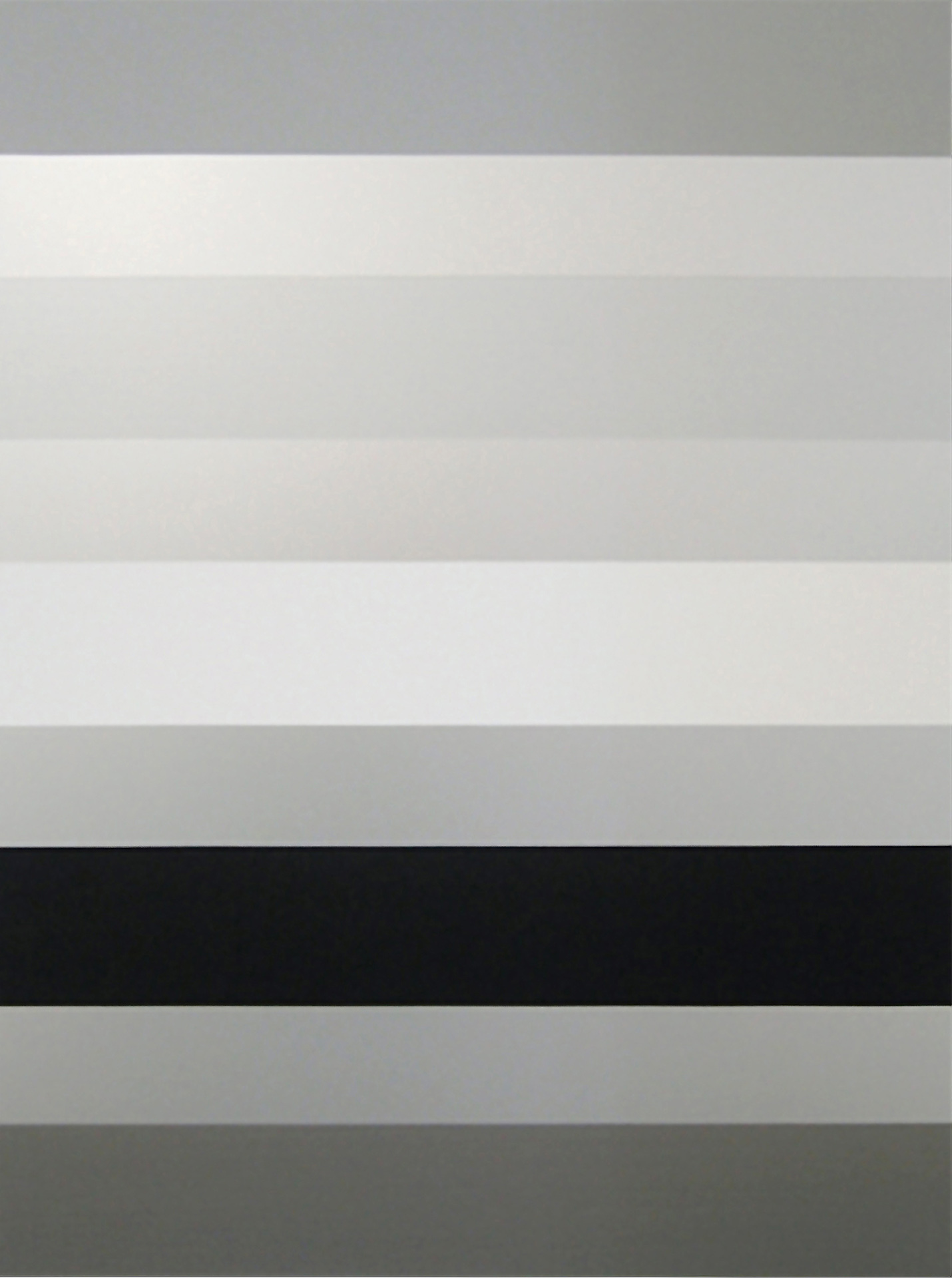

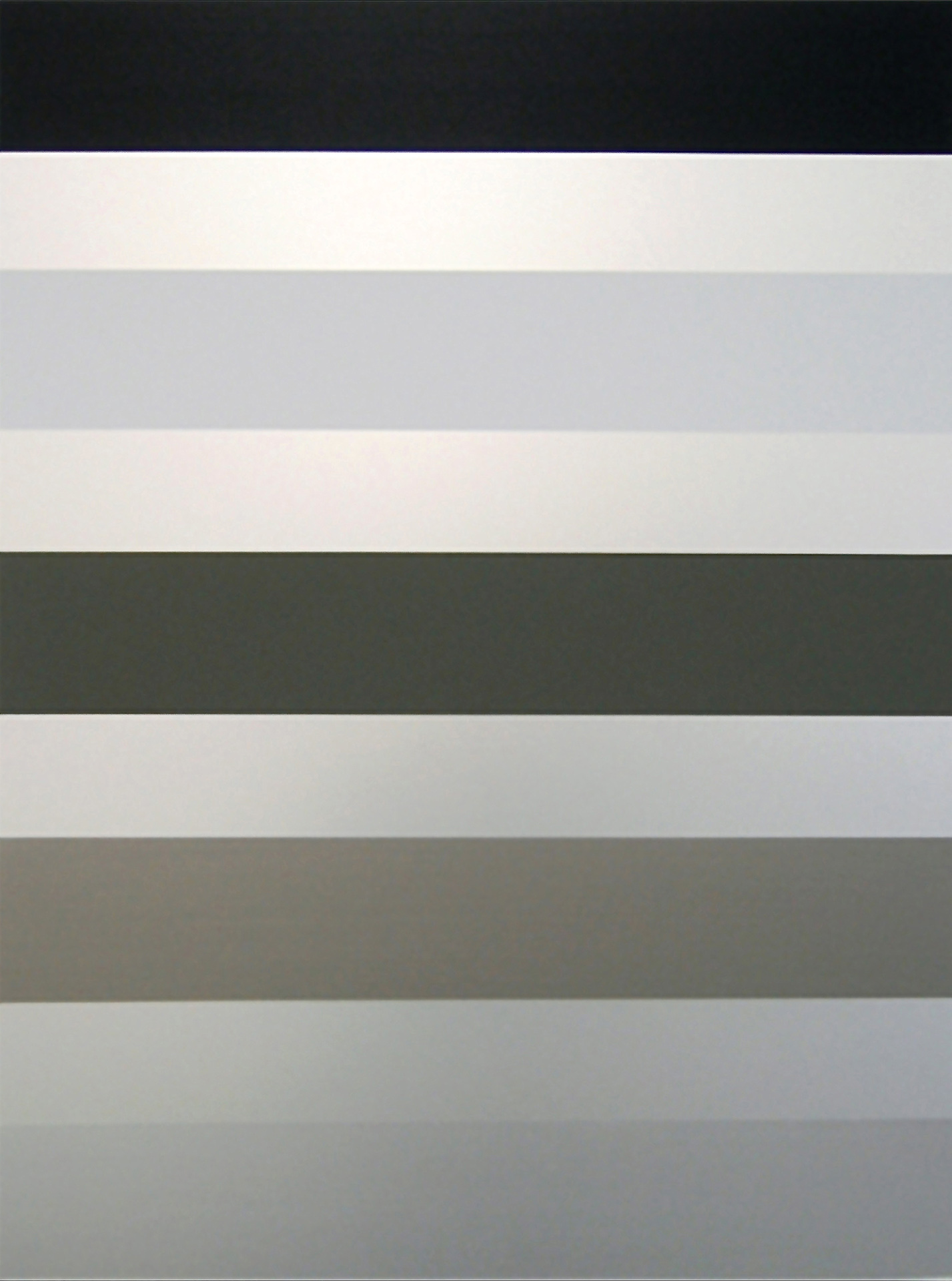

DG: One temporary work I made in 1994 in Switzerland was an allover tape work in a big factory, at that time used as a cultural center with guest studios. It was a beautiful space, but the view had been blocked by many movable walls, and a lot of things were lying around for a long time. I decided to take out all the walls to empty the space and to clean the floor. Then I mounted horizontal bands of black adhesive tape onto three outer walls, and also horizontal bands of clear tape around three sides of the freestanding inner coloumns. The whole space only changed a bit, but it was the first time visitors could see the space itself in a new way, only slightly changed.

Another work I made was in 1998 at the newly opened Kunsthaus Baselland. It was the very first exhibition there, and I had the chance to use the whole basement space to make one big installation. The idea was to introduce the space itself to the visitors. I made a concept for all the walls and the floor using black adhesive tape in different widths, clear tape, and green artificial carpet.

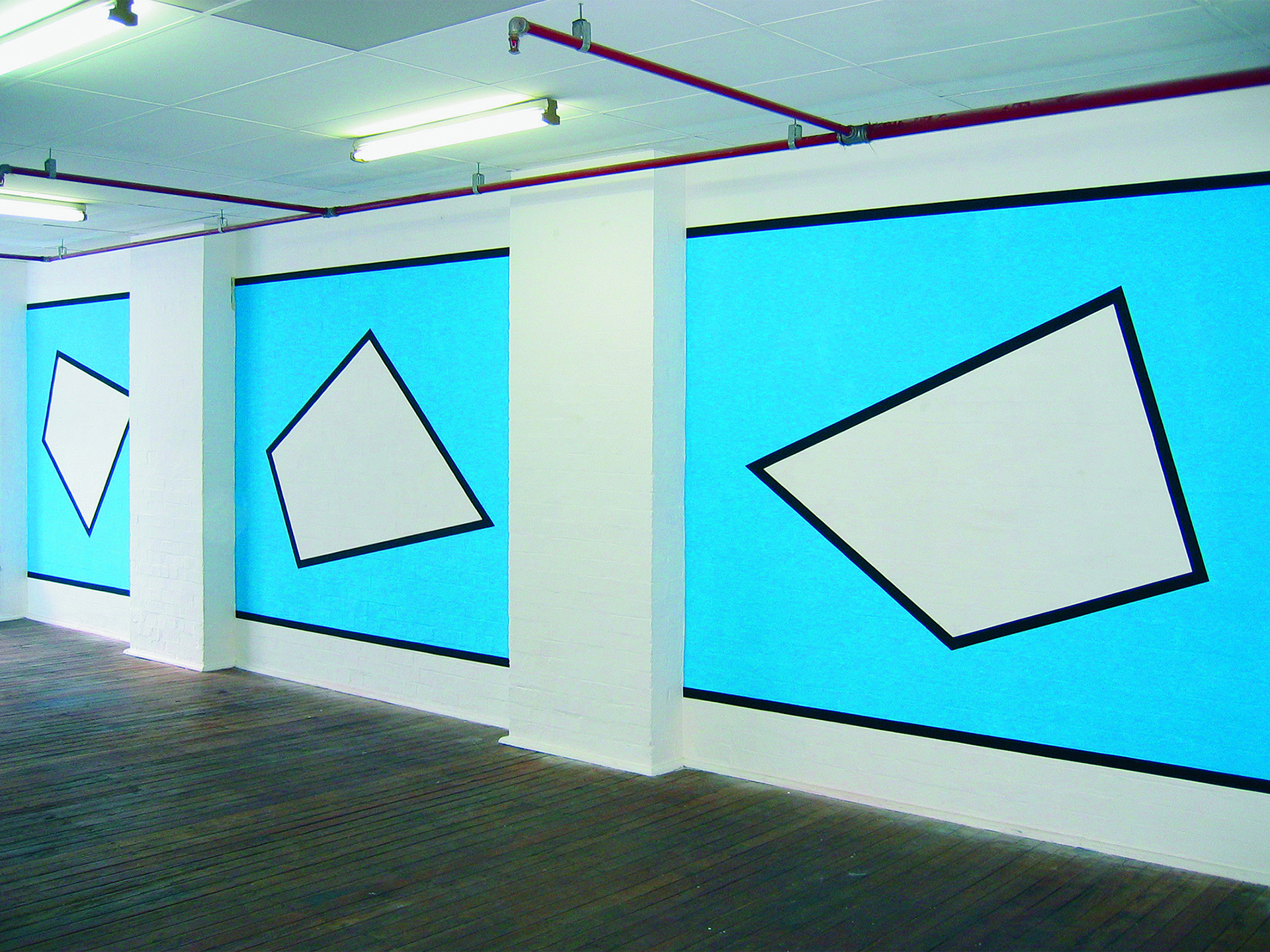

A third exhibiton I made in 2001 was at the Haus für Konstruktive und Konkrete Kunst in Zürich (now called Haus Konstruktiv, in a new place). This place is the heart of the first, second and contemporary generation of Schweizer Konstruktivismus and Konkrete Kunst—Max Bill, Richard Paul Lohse, Verena Loewensberg, Fritz Glarner, Camille Graeser, Hansjörg Glattfelder, Beat Zoderer, and others. I decided to paint the walls of four spaces in four different colours, and put an allover network of black adhesive tape entirely across each of the walls. The first space was painted green, and I placed a Le Corbusier sofa from the office of the museum onto a blue artificial carpet. A small radio stood in the corner playing a daily program. The second space was painted yellow and was left empty. The third space was painted orange with the model of the new museum standing on a blue carpet as well. The last space was painted pink, and visitors had the possibility to see images of the renovation of the new museum on a computer, which was also standing on a blue carpet.

These three examples are installation works dealing with a real situation, time factors, and artistic and non-artistic conditions. If I can say each was successful, it was maybe because of the treatment of the whole situation, and an unusual use of usual industrial materials in a subtle way.

CA: There are of course precedents for site-specific wall works. Probably the two most important contemporary figures noted for their wall installations beginning in around 1968 are Blinky Palermo and Sol Lewitt; each is noted for his handling of space and his process for working, and the resulting work cannot easily be called painting, sculpture, architecture, or even decoration. In 1979 an exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago called “Wall Painting” included Robert Ryman, Marcia Hafif, Lucio Pozzi, Richard Jackson, and Robert Yasuda; this exhibition seems apart from your approach since it primarily focused on moving painting from the canvas to the wall. Currently, David Tremlett makes large wall drawings using imagery and color inspired by his travels. Jan van der Ploeg, your contemporary, makes wall paintings that have a conceptual basis and which, I think, seem to flirt with a pop-influenced, neo-modernist decoration. Even earlier are the examples of Schwitters and El Lissitzky’s “Prounen Raum.” And of course, there is also the long history of frescos and murals. How do you see your work in this history? What are some of the concerns that you share with these artists, and what do you see as unique to your work?

DG: The concern that I share with many of these artists is the fact that the wall is not only a wall to which the work is applied; it is an active part and support of the work at the same time. Many wall works stay in line with being a painting on the wall not linked to the site. The wall remains the background for the painting with its motiv coming from somewhere else. Architectural-spatial specialties and details are more hidden or covered rather than consciously included. I see the unique part of my work in the presence of the existing wall including details (doors, switches, plugs, tubes, and other irritations) and the motiv at the same time. It is what I would call concrete. The way of reading the work is reading one thing. The existing wall makes the work visible, the work makes the existing wall visible, and seeing both simultaneously makes the artwork visible. One of the concepts I am using since 2000 is a myriad of adhesive tape lines I attach directly to a wall or floor, one line after the other. It’s the idea of doing something the same or similar, step by step, again and again. The making itself can be monotonous, repetitive, meditative, interesting, boring, like an everyday job. It’s again doing instead of not doing, and after a while one sees something appearing while the labour itself disappears. The work becomes independent and self-evident, normal as a table, a door, a real thing. The difference between high and low is gone.

CA: The image made with tape in these wall works isn’t planned ahead, but you make it on-site in response to the wall as you encounter it.

DG: The recent wall works (Networks, since 2000) made with adhesive tape are based on a flexible concept. There are a few things I plan ahead concerning the site. The image is roughly planned as a starting-point. With the execution of the work I get additional information from the site, which sometimes requires a change or an adaption. I start working somewhere by mounting the tape directly to the wall. Then a door, a window, a pipeline, a staircase and so forth blocks the flow of the work, and it forces me to respond. This influence can change the rhythm and direction of the work. Therefore the work links with the site directly. This work will be different from the last one or the next one. The continuity is in the similarity and in the difference of both the works and the sites.

CA: Some of your wall works cover a complete wall from side to side and floor to ceiling, and others are framed on the wall, separate from the edges. My initial feeling about this is that a covered wall becomes an enveloping environment, whereas one that does not extend to the edges of a wall is framed somewhat like a picture on a wall. How do you see these differences?

DG: Yes, it’s different. The allover work uses the whole size and architecture of a wall or a space. A framed work is usually built in relation to the proportions of the site, too, but the focus and the visual reading is different. The framed work focuses the view inside the frame, where the wall is part of the work, and outside the frame is the support. The allover work spreads in all directions; there is no focus, and the wall is a part of the work and the support at the same time. In some installations I combine both systems—convergent and divergent views.

CA: Do you use a wall as you find it, or do you prepare the wall? Do you change the color or surface texture?

DG: The quality of a wall or floor is part of the conditions I mentioned above. I try to accept a space as it is at first sight. The quality of a wall is a given; there is no reason to change it. A dirty wall with spots, holes or scratches is site-specific; I like to include these tracks. I make the experience so that the mounted (especially black) adhesive tape freshens up the wall as a whole spatial situation; visitors many times think that the wall has been pre-painted. It is not the idea of a pure art work I make; it’s more a kind of collaboration between the existing and the new. Ilya Kabakov talks about the total installation, which in my mind is a special case, since the work denies the existing space many times (dark spaces), as do some of James Turrell’s installation works, in a similar way. It takes the viewer away from the real space he is in. That is what I try not to do.

CA: One of the difficult things I would think your wall works force you to confront is the delicate balance between art and decoration, especially when a wall work is in a more public space as opposed to a space that is recognizable as a context for art. I’m reminded of this by the Christine Mehring paper “Decoration and Abstraction in Blinky Palermo’s Wall Paintings” (Grey Room 18, Winter 2004). What are your thoughts about art versus decoration? Do you care about this? Are there things that you do in the work to steer the viewer towards one way of seeing or the other?

DG: My concern is to build a concrete visual identification for a site, created by an art work linked to the site to evoke a situation in reality that can make sense there. The aspects of the site influence the concept I develop. I am interested in a work that makes the site visible through the art work, and the site makes the art work visible at the same time. It is about the consciousness of perceiving something. It is a communication, a give and take between equal parts creating a new, balanced entity. It is a two-way system, different from a one-way system or a non-linked idea projected onto a so-called neutral ground, which I would understand as decoration.

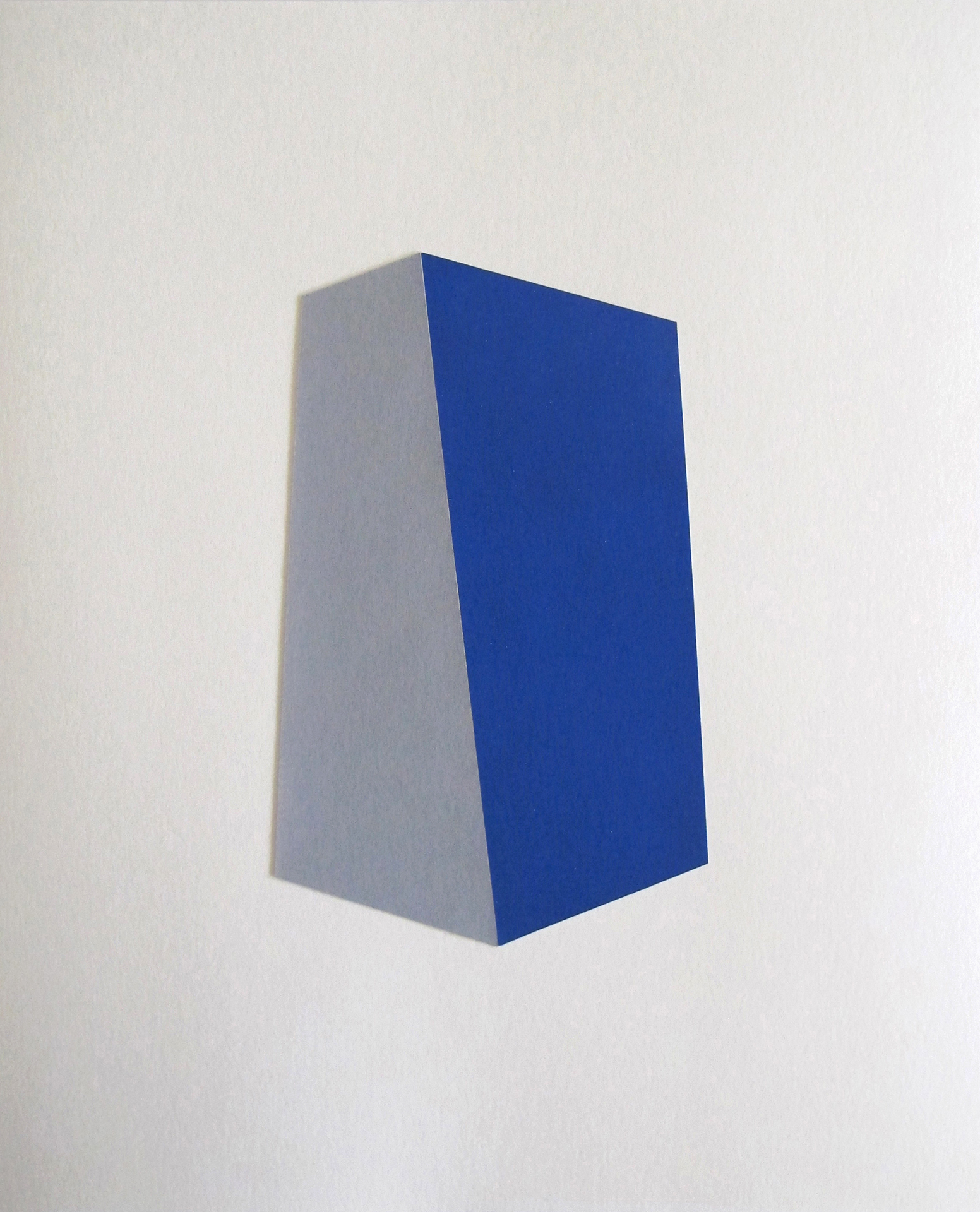

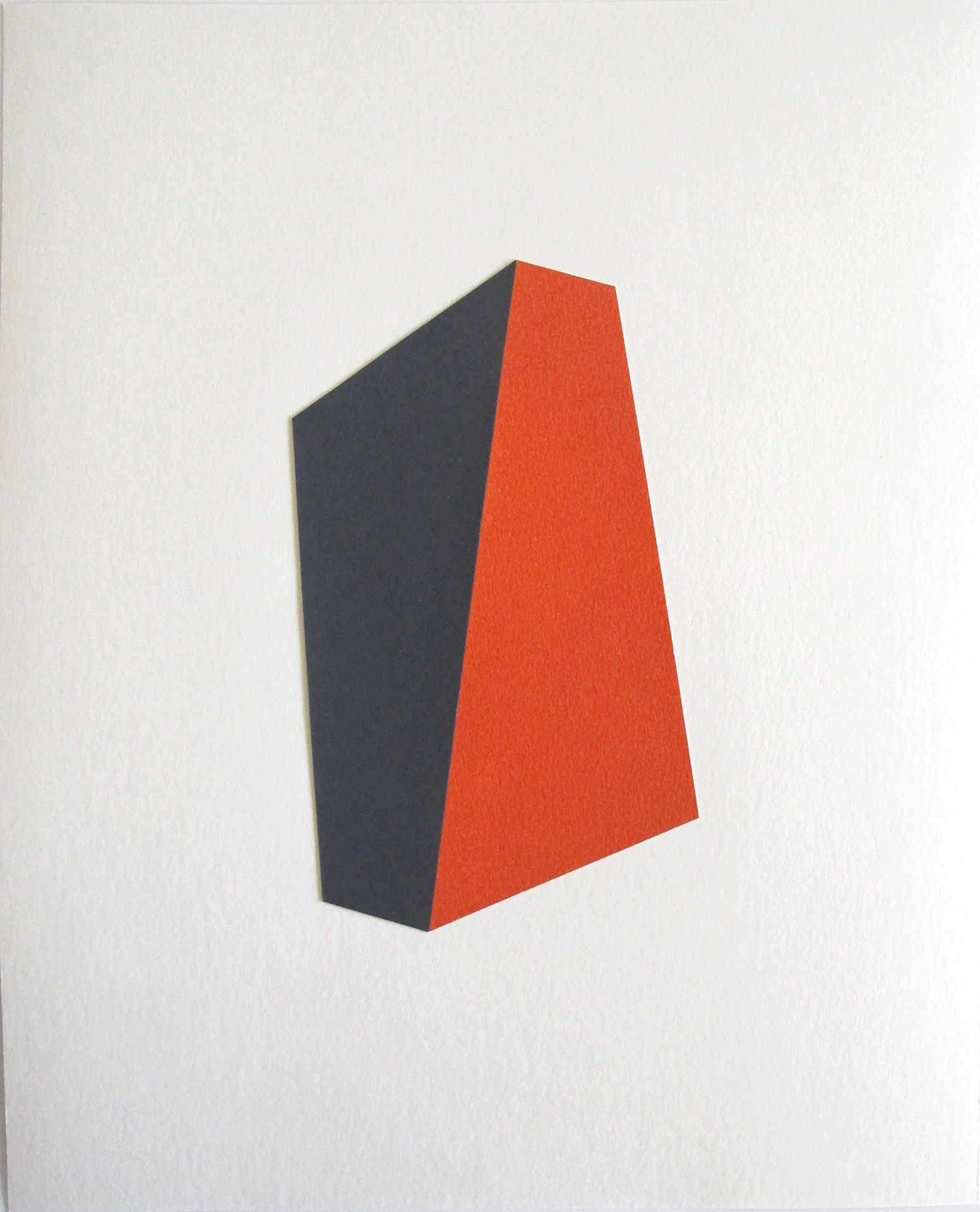

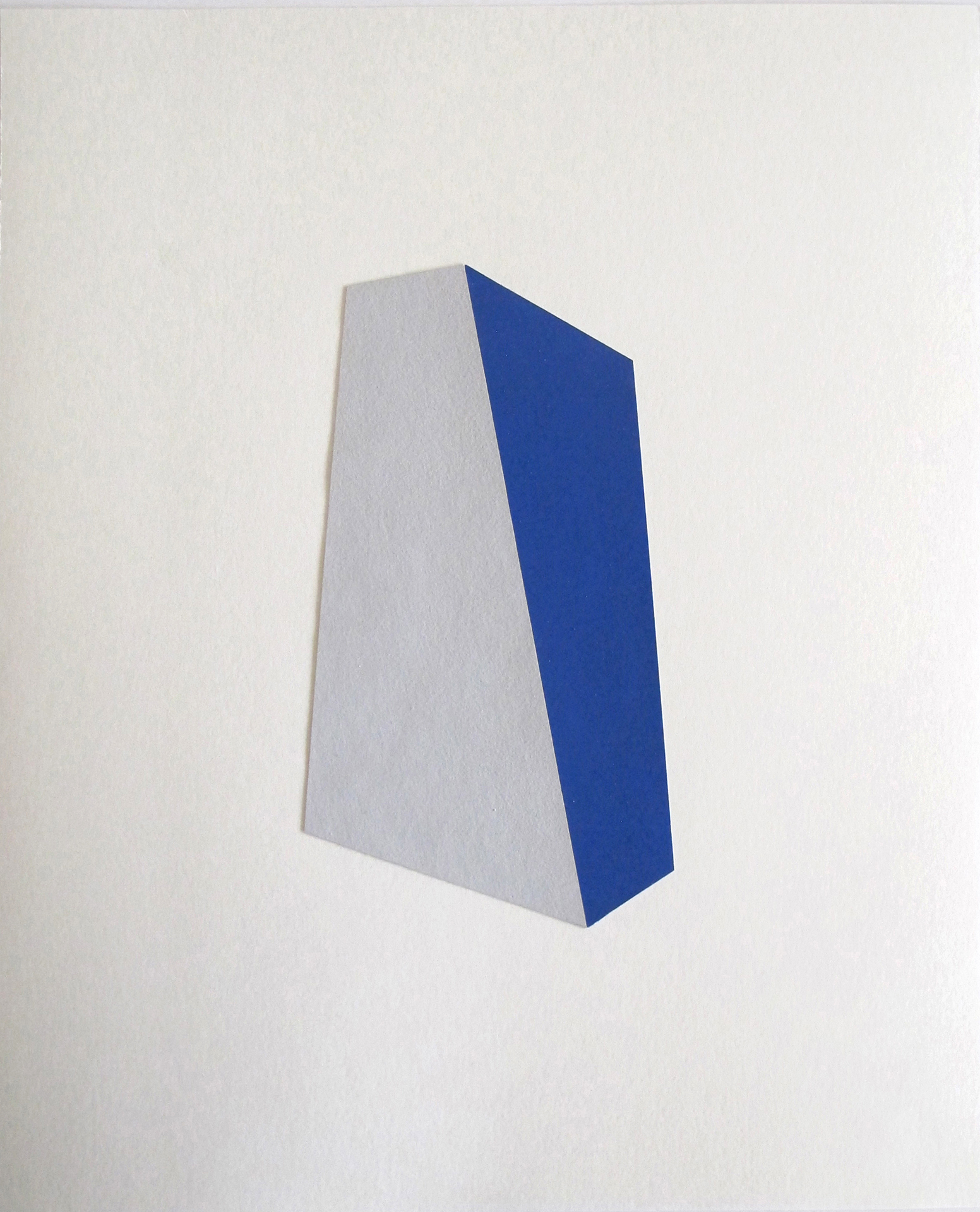

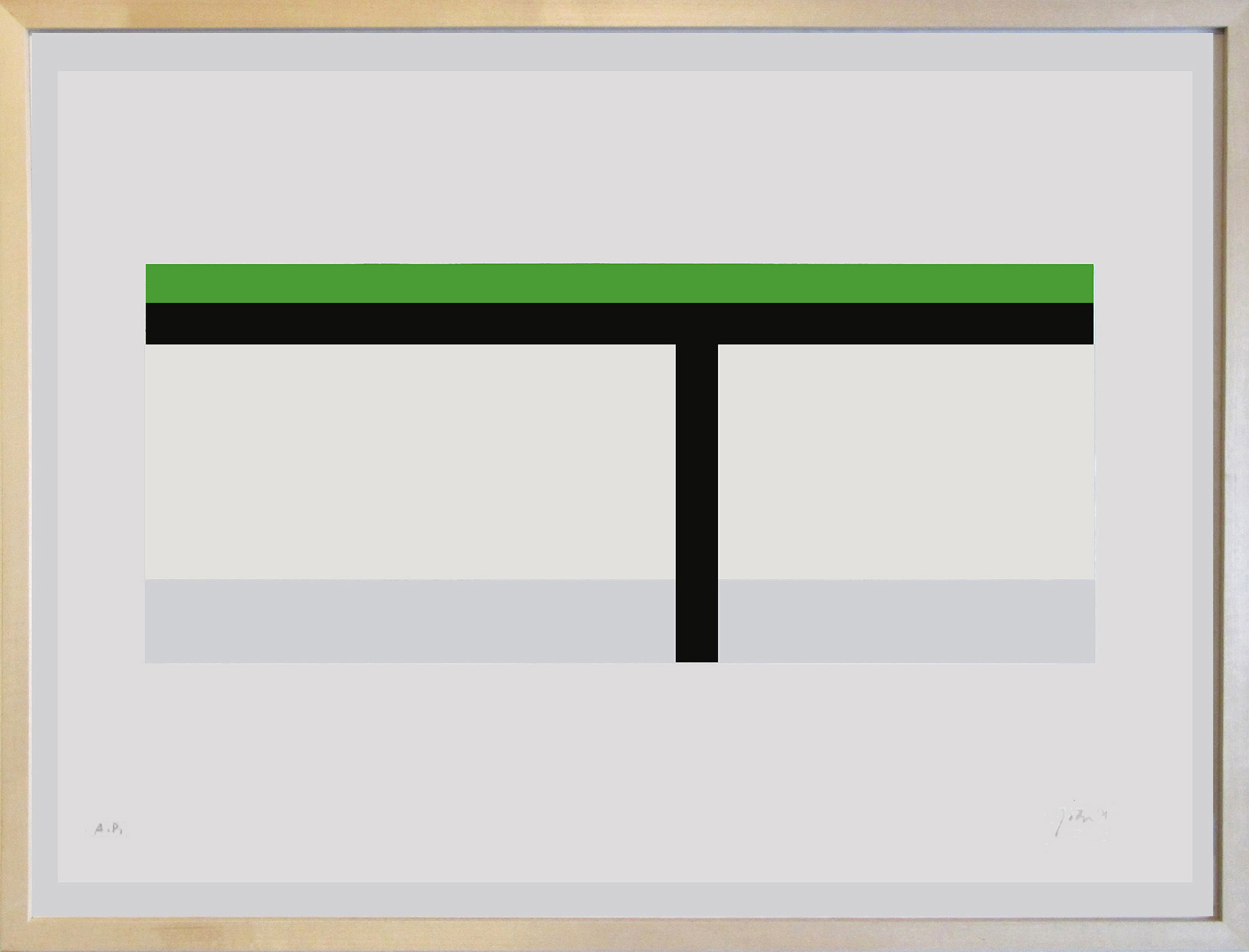

CA: You seem to use images in the wall works and the objects that have aspects in common. You have recently used what you call a “diamond” shape in both the wall works and the objects; it’s a four-sided shape, and sometimes it looks like a square in perspective. Also, the objects that you have made that look like skewed crosses seem like details from the wall works where two taped lines cross at an angle. Is this a relevant observation? Is this a common practice for you?

DG: Yes, some details of a work can develop into an independent new work sometimes. Since I like to work with basic and simple geometric forms the field is limited. The limitation enables me to use a language with similar forms, patterns or grids in different ways. Many times it is playing and reflecting between the same, the similar, and the different, making distinctions visible. I usually work simultaneously on different projects. The public works or commissioned works have specific demands. Other works I make without a specific connection to a site, but connected between different types of my works. It is working in a two-way system, which is reflected in work made in new ways or from a new point of view. A prolific communication takes place between my various works. It shows several aspects, and results in my art work as an allover entity.

CA: You don’t call the objects you make paintings, right? When you make these objects do you have more options than the industrial materials you use for the wall installations? In particular, I wonder if you have more choices in terms of color, support, and surface than you do for the wall works.

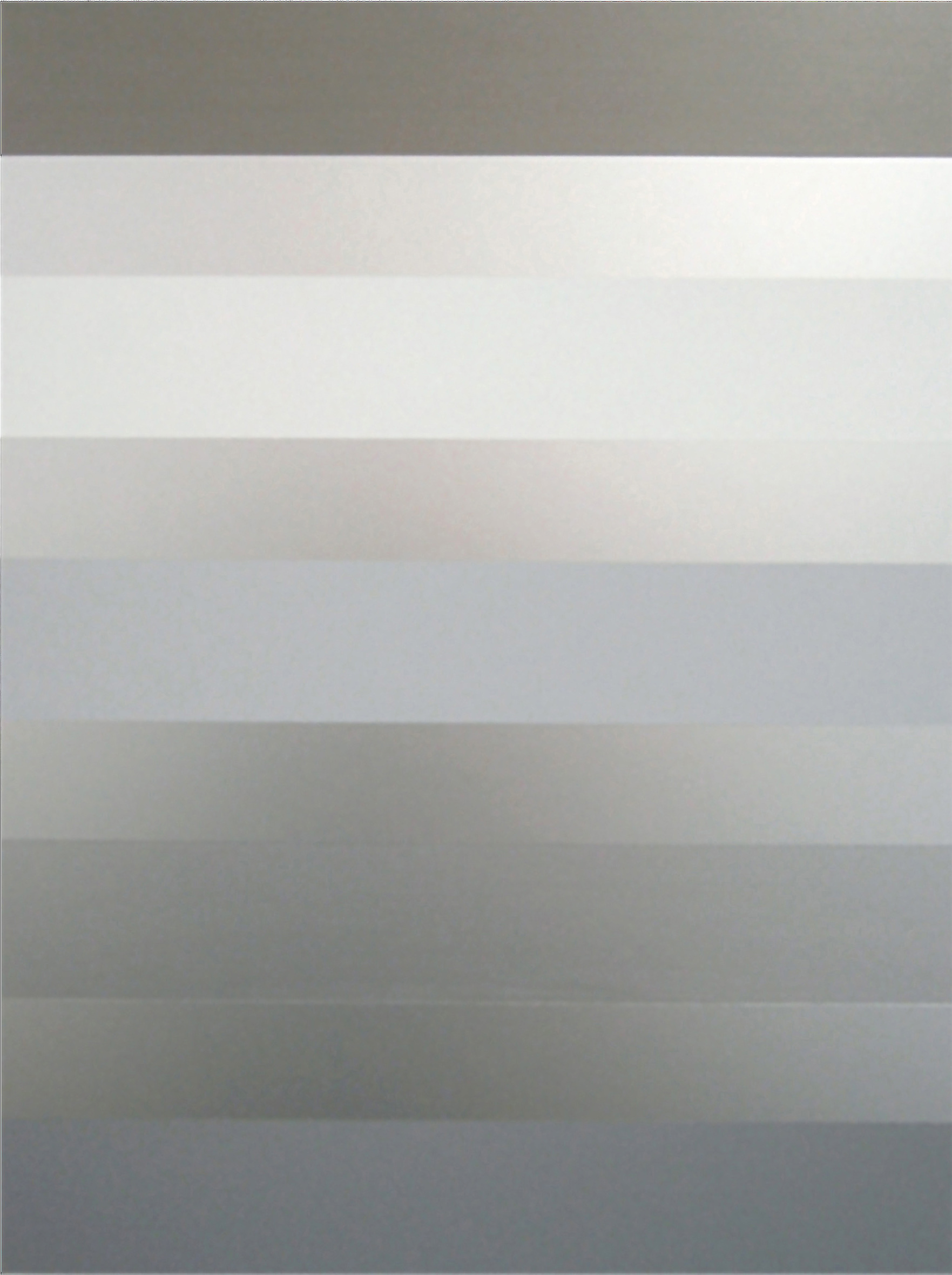

DG: Since my background is closer to three dimensional work—sculpture and architecture— than painting, I would rather call the works objects, though some of them are very close to painting, or even are paintings. Many of the works are built or constructed; they have a third dimension, and they have color or colored parts. Some works are based on the distinction between the color of the support and the applied color, which is related to the example mentioned above about the wall and the applied tape for an installation. I don’t work with a specific color system, though I use color very often. I usually apply color flat on the surface. The use of material, and the way a work is constructed, shaped and joined together is very interesting, and color is a factor I use very spontaneously. Of course, there are many choices in using color for objects and paintings, and prefabricated, standardized industrial material is very limited in color and in size. Working within these limitations and materials is challenging; it is connected to the everyday working world. The ordinary materials and the way of making a work of art connects it to everyday working processes and techniques.

CA: Do you ever combine an object with a wall work?

DG: Sometimes I combine them. In some cases working on a concept leads towards a combination. Some exhibitions or sites ask for a combination of two and three dimensional work. The tape is flat and rather two dimensional, and many objects are three dimensional. An object mounted on the wall calls for a focused, detailed view, and an allover tape work calls for a distant and broad view. It’s again a two-way system that simultaneously shows distinctions between an object with its own quality in any place, and the tape that only exists on a specific site. Both are equal parts to be perceived together with the wall or site. Using many different entities simultaneously can be an aim in the future. I could imagine combining different or even contary movements in art (and life)—a combination of, for example, Schwitters and Judd, is not really a contradiction to me. Of course there would be many other interesting possibilities.

CA: I am interested in the viewer’s experience of your work. The wall works make an environment around the viewer, and so there is an element of time and movement in looking. The objects are more static, more like icons that have a one-to-one physical relationship with the viewer, which is a way of looking that is not so much about movement or time, and more about stillness. Considering the images in both the wall works and the objects, they can be split very roughly into two groups: imaes that appear to be solid objects, and those that are linear objects. Viewing each of these is a very different experience. To put it very simply, as a kind of concrete example, a “Diamond” work on aluminum from 2004 is like a landscape, whereas one of the shaped crosses made of MDF from 2002 is a kind of figure. Images in the wall works can also prompt these associations, which are part of how the viewer might begin to physically and metaphorically respond to your work. What kind of visual, physical, and metaphorical responses are you hoping to invoke with your work?

DG: My focus is not so much on the responses my work can invoke. I understand the response as a result of what I do. I would like to create a free field of associations that can lead to the viewer’s own conclusions. Something is there without an explanation. The art work doesn’t need a reason to be—it simply exists, like anything else in the world. It is a realized possibility besides many other possibilities. The art work is not a solution for something else; it is something to reflect on, and it is an independent companion. The viewer experiences the art work immediately in real time and space. I do not intend to make art that creates secrets or longings. My concerns are existence, position, orientation, material, construction, proportion, distinction, repetition, contemplation, and stillness. I like the idea of an artwork that makes sense without a reason.

The viewer’s response begins with an exhibition. That’s the moment when the artist’s work is finished and valid. There is no way back, and no change possible. The responsibility and the risk for the work is on the artist’s side. The viewer’s response is the part coming from the outside. As mentioned before, all elements seem to be based on a two-way system. It’s a dualism.

The use of the terms “landscape” and ‚figure’ are not very important to me. I try not to serve this kind of looking at art. To me it is a pre-determined way of thinking that is unimportant for my work, since my work is spatially oriented and not representational. The terms “reductive” and “abstract” I understand in a similar way, as a derivation from something else that has been either more or bigger. I prefer the terms “object” and “concrete”, which I think are the closest to what my work is.

I don’t work towards a specific aim. I am working permanently on different projects, and they all begin anywhere in the middle of nowhere; they are not yet defined. I understand my part of the work in developping a concept and realizing the work, and the other part of the work would be the viewer’s view, experience and response. I understand art as a provision for life, like food and sleep. Art speaks to the senses; it offers a wide range of contemplation the viewer can reflect on, and it can enhance his or her consciousness of things in life.

Since visual art is basically a individual enterprise it mainly shows a single point of view towards the world. My work is one position realized. It is up to the viewer to get an impression of the work. I don’t think that art necessarily has to be understood by explanation. It is one of the free fields which is allowed to be left open. People can take the visual experience of an art work without possessing it. Art should not only be shown in a context of art, it should also happen in everyday places. This is one reason why I like to work in a flexible way . There is a difference between art lovers going to the galleries and museums, and art going to meet people. It is a universal language for everyone. My work is based on simple elements like a line, a field, a geometric form existing in the world already. I use them by putting them into a new spatial context.

It is my intension to make artwork in a concrete sense. To me concrete means a work existing on its own, like any other thing in the world.

CA: Something that allows art to remain an open field, as you call it, is that it doesn’t necessarily have a practical function— it’s not useful or utilitarian in the sense that we think of when those words are applied to everyday objects. As I understand it, the classic defintion of Konkrete Kunst, beginning with Van Doesburg and continuing through Max Bill and Richard Paul Lohse, doesn’t concern itself with abstraction, and certainly possesses no symbolic meaning, but is more or less concerned with an idea expressed visually through geometry. Is that where you begin?

DG: Partly yes, but for me that’s only half the story. Art history sometimes pretends that a particular art movement is a complete entity. Using the term “concrete” doesn’t necessarily coincide with the ideologic background of Konkrete Kunst, which was also based on ideas about society and politics. My concern is about an entity that can also include contradictions—a yes and a no, and even a maybe. My starting point is a synthesis of different views or positions at the same time, which to me is a spatial view. It can be obvious or subtle, symmetric or asymmetric or both together, with or without contradiction. It can be rule and deviation together. Some of the earlier works I made were collages related to Kurt Schwitters’ work (Merz), any found material roughly glued onto a piece of cardboard— physical, direct, improvised, accidental, colourful, even Dadaistic. Later, I became interested in Minimal Art, where the artwork is often precisely planned, and perfectly and clearly constructed with a defined use of materials and attention to details. Both movements are important to me, and sometimes I see my work carrying parts of both, corresponding in between those two art historical position.

CA: Regarding the function of art, which relates to content and meaning, as I see it art objects do have functions, whether it is for description or depiction, or for contemplation, beauty, or pleasure, or a demonstration or articulation of a critical or philosophical ideal or model, and so on. Typically, this is a visual experience, though not exclusively. Any of these functions are part of what make an art work “a work existing on its own,.” Is this part of what you mean by a concrete work, or are you more specifically referring to physical and contextual characteristics?

DG: The art work as “a work existing on its own”emphasizes mainly its own physical existence. The functions you mention above are rather functions or directions for the visual experience and the use of the viewer, not necessarily functions of the art works. Of course, the way a work is built and installed in a context can evoke different visual experiences. The work is there because there is first a floor or a wall, a spatial situation that provides a position. The physical work doesn’t exist in a non-space, it needs surroundings to exist. Maybe thoughts, dreams, or an idea can exist in a non-physical space, but doesn’t it still appear in a spatial situation?

I like a work that exists on its own together with its spatial position. This doesn’t say anything about the content of the work itself, because the whole situation is the content. Since everybody lives in a spatial situation, the viewer can experience this freely. Visual (and physical) perception is existential and important in everybody’s life. My concern in art is about visual experience and perception in general: a focused view combined with a broad view; a view from above combined with a view from below or from behind; a view from the inside and from the outside; and a view from all different positions. I try to bring them together again equally.

_______________________________________________________